Fear

Fear is the mind and body’s built‑in alarm response to danger. It’s what helps a person detect threat, focus on it, and prepare to fight, flee, freeze, or otherwise protect themselves. When fear works well, it keeps people alive; when it misfires or gets stuck “on,” it can turn into anxiety problems.

What makes a person fearful

Fear arises when the brain decides something is threatening: a loud noise, an angry face, a memory, a thought, or even an internal sensation like a racing heart. The amygdala and connected circuits quickly scan for danger and can trigger a fear response before conscious thought catches up.

Why some people are more fearful than others:

- Genetics and temperament – Some individuals are born with more sensitive threat systems; they react more strongly and learn fear more easily.

- Learning and past experience – Fear conditioning research shows that when a neutral cue (place, sound, situation) is repeatedly paired with something aversive, the cue itself starts to trigger fear. trauma, bullying, or repeated criticism all shape what feels dangerous.

- Generalisation and stress – In some people, fear “spreads” too widely from one threat to many similar cues, a pattern linked with anxiety disorders. Chronic stress can also make the amygdala more reactive and reduce the ability of the prefrontal cortex to calm it.

So a fearful person is not weak; they typically have a more sensitive alarm system, shaped by both biology and experience.

The psychology and brain circuits of fear

Psychology and neuroscience see fear as:

- A rapid defensive response: changes in heart rate, breathing, muscle tension, attention, and motivation (urge to escape or defend).

- Driven by a threat‑processing network: the amygdala and extended amygdala, hippocampus (context and memory), insula (body sensations), and prefrontal areas that can either dampen or amplify the response.

- Acquired and updated through learning: people learn what is dangerous (and what is safe) through direct experience, observation, and stories, and these associations can be strengthened or weakened over

When this system is balanced, fear switches on for real threats and off when the danger passes. When it is dysregulated- through genetics, trauma, or chronic stress, it can trigger too easily, last too long, or fail to distinguish between genuine danger and safe cues, contributing to phobias, panic, and PTSD.

People become fearful when their life history and wiring teach their brain that the world is more dangerous than it may actually be. The psychology of fear is about how the threat system is tuned, how it learns, and how it can be calmed and retrained.

Fear of Societal Toxicity

Fear does not come only from someone’s biology and personal history; it is also constantly shaped and amplified by other people, by social structures, and by media.

Social and interpersonal “fear programming”

Families, schools, workplaces, and peer groups teach – often without saying it directly, what “must” be feared: failure, rejection, humiliation, poverty, being different, breaking rules, or challenging authority. Repeated criticism, shaming, bullying, or emotional unpredictability from others trains the Nervous system to expect danger in everyday situations, not just in objectively life‑threatening ones.

Over time this can create:

- Social fear – of being judged, excluded, or attacked.

- Performance fear – of making mistakes or not meeting expectations.

- Identity fear – of showing your real self and being rejected.

These are often rational in context: if your environment punishes difference or failure harshly, fear is a realistic adaptation.

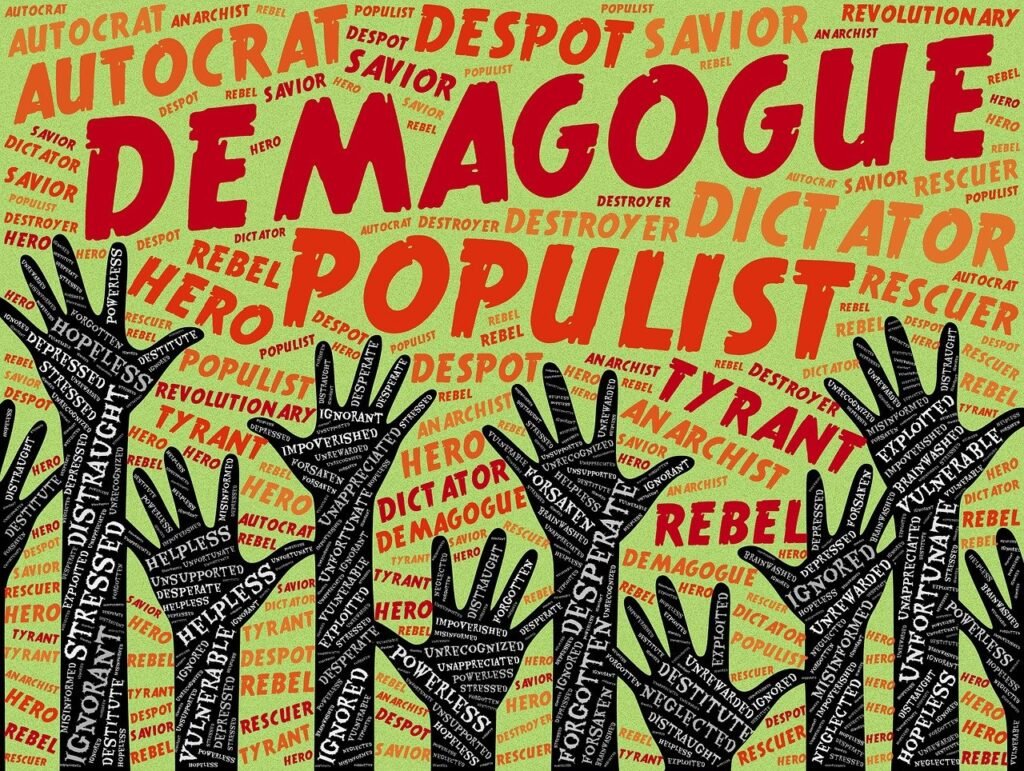

Cultural and media‑driven fear

Media and politics frequently use threat‑based messaging – crime, disease, economic collapse, “dangerous” groups, in order to grab attention and shape behaviour. Reviews of news and social media content note a consistent emphasis on risk, conflict, and crisis, because fear and outrage keep people watching and clicking.

This does two things:

- Keeps the threat system chronically activated: the world feels more dangerous than personal experience alone would suggest.

- Narrows focus to survival themes (safety, status, in‑group vs out‑group), which makes people more anxious, more easily manipulated, and less open to nuance.

There is “genuine need for fear” in the sense that many real systems (economic, political, social) are organised in ways that punish missteps and reward vigilance. But there is also inflated, profitable fear: manufactured or magnified threats used to control attention and condition behaviour.

What makes people fearful is not just their amygdala and past trauma; it is also living in environments – families, communities, media ecosystems, that repeatedly tell them “you are not safe, you are not enough, and danger is everywhere.” Recognising that social layer is essential if the goal is to help people tune their fear back toward what is actually necessary.

Irrational Fears

Fear can be rational or irrational, but in real life the two often get tangled together, especially under the influence of media and hidden social stories.

Rational vs irrational fear

Rational fear: Fear that matches a real, present or likely threat. Examples: stepping back from fast traffic, leaving an abusive situation, worrying about losing income in an unstable job. Here, fear is proportionate and protective.

Irrational (or disproportionate) fear: Fear that is much bigger than the actual risk, or attached to something that is not truly dangerous (for example, extreme panic on a safe lift, intense terror of harmless social situations). This often comes from over‑generalised learning, trauma, or misinformation.

The problem is that the nervous system does not label fears “rational” vs “irrational”; it just reacts to what it has learned to treat as threat.

How media and hidden narratives distort both

Modern media and many social narratives tend to exaggerate threat signals across the board:

- News and social media focus on rare, dramatic dangers (violent crime, disasters, extreme opinions), making them feel common and close‑by.

- Political and cultural stories quietly tell people who and what to fear: certain groups, failures, non‑conformity, speaking out.

This does two things at once:

Amplifies rational fears: Real risks (crime, illness, economic instability, discrimination) are presented in a constant, high‑volume way. The result is chronic alertness far beyond what is needed to stay reasonably safe: people feel under siege, even when their immediate environment is relatively secure.

Breeds irrational and myth‑based fears: Repeated stories, Stereotypes, and rumours teach fear of things that are exaggerated or false (for example, whole groups portrayed as dangerous, or everyday behaviours framed as highly risky). Over time, these socially learned fears can feel just as compelling as those based on direct experience.

Because these messages come from “trusted” sources (news, community, family, culture), the brain treats them as evidence. Rational and irrational fears then blur: people feel frightened but cannot easily tell which fears are grounded and which are products of narrative and repetition.

The overall confusion

The result is a noisy inner landscape where:

- The body’s alarm system is over‑tuned, firing for both genuine dangers and socially inflated ones.

- People struggle to distinguish “this is a real, present risk I need to act on” from “this is a story I’ve been fed, or a rare danger presented as constant.”

- Fear feels justified everywhere, which makes it harder to calm down even when logic says you are safe.

In short: Rational fear is necessary; irrational fear is learned; and media plus hidden societal narratives often push both into overdrive, creating a generalised fearfulness that is out of proportion to everyday reality. Learning to question sources, check actual risks, and notice when fear has been socially “programmed” is key to reclaiming a more accurate sense of what truly deserves your alarm.

Further Reading

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2882379/

https://www.sciencefocus.com/the-human-body/the-science-of-fear-what-makes-us-afraid

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3062636/

https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/blog/think-act-be/201603/where-do-fears-and-phobias-come

https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/f9a00aa20b53ba20b22f9a9d5f1a8931392773e1

https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/blog/the-mood-lab/202509/the-fear-of-differences

https://www.sciencefocus.com/the-human-body/the-science-of-fear-what-makes-us-afraid

https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/blog/think-act-be/201603/where-do-fears-and-phobias-come

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8617299/

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2882379/

https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/f9a00aa20b53ba20b22f9a9d5f1a8931392773e1

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10960960/

https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/blog/the-mood-lab/202509/the-fear-of-differences

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6993823/

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2882379/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15963650/

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6861247/

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4424059/

https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/blog/think-act-be/201603/where-do-fears-and-phobias-come

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3062636/

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8617299/

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41398-019-0646-8

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3181834/

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10960960/

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4417372/

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9035063/

https://acamh.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jcpp.12316

https://doi.apa.org/doi/10.1037/a0017551

https://energypsychologyjournal.org/what-does-energy-have-to-do-with-energy-psychology/

https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/55bfcdd15d5d3ecd16b9f48c6f3bf537431265dc

https://lebs.hbesj.org/index.php/lebs/article/view/lebs.2021.84

https://drum.lib.umd.edu/handle/1903/20044

https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/animsent/vol3/iss22/9

https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/b339cf4a0bcbafcdb5dc804640326de168956981

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07287.x

https://www.jneurosci.org/content/jneuro/early/2021/11/05/JNEUROSCI.0857-21.2021.full.pdf

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2580742/

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6730310/

https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/24894-amygdala

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4115032/

https://www.webmd.com/brain/amygdala-what-to-know

https://www.healthline.com/health/stress/amygdala-hijack

https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/blog/the-mood-lab/202509/the-fear-of-differences

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0191886923003069

https://www.simplypsychology.org/amygdala-hijack.html

https://www.reddit.com/r/ask/comments/wf7jvc/why_are_so_many_humans_scared_to_be_different/

https://www.facebook.com/groups/443432570174709/posts/1428817898302833/

https://www.sciencefocus.com/the-human-body/the-science-of-fear-what-makes-us-afraid

0 Comments