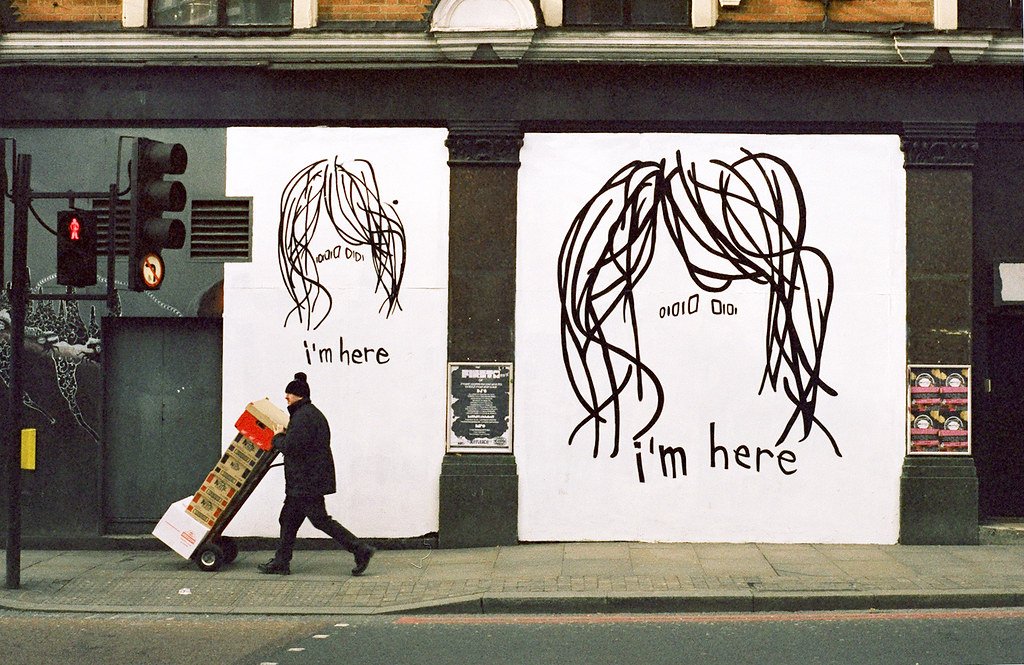

“attention seeking” by jonny2love is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Showing Off

Showing off is something many people do when they feel small inside, not big. It often comes from pain, not pride.

What “showing off” really is

Showing off means exaggerating the truth, or even making things up, to impress others or get their attention. On the surface it can look like:

- Boasting about achievements

- Pretending to know more than you do

- Acting bigger, richer, smarter, or kinder than you feel inside

But underneath, it is often a way to say: “Please see me. Please value me. Please tell me I matter.”

Where it often comes from

For many people, this pattern starts in childhood. If a child’s caregivers are distant, critical, distracted, or neglectful, the child does not stop needing warmth and safety. Instead, they try other ways to get seen and loved. One common way is to perform: to impress, to entertain, to be “special” so someone will finally care.

Over time, the person may:

- Stop believing that their real self is good enough

- Learn that love seems to come only when they are interesting, impressive, or useful

- Feel a hidden, painful sense of being “less than human,” or broken inside

As an adult, showing off can become a habit that hides a rock-bottom sense of worth. The louder the outside, the emptier the inside often feels.

Why people lie or exaggerate

When someone lies about who they are, it is usually not because they are evil or “just a liar.” It is often because:

- They have lost trust in their real self

- They think the truth of who they are is boring, shameful, or unlovable

- They are terrified that, if people saw the real them, everyone would leave

So they build a mask: a more confident, more successful, more exciting version of themselves. At first, this mask may feel like protection. But later, it can feel like a prison.

The mask and the shame underneath

Over time, the mask can become more comfortable than the real self.

- The “show-off” self gets praise, laughs, or admiration

- The quiet, wounded self feels ugly, weak, or “not human”

This can lead to deep shame:

- Shame about not being honest

- Shame about needing attention

- Shame about feeling empty without the act

But that shame is built on a misunderstanding: the belief that only a fake, polished version of you deserves love. That belief is not true.

Meeting “showing off” with empathy

If this description fits you, it does not mean you are bad or broken. It means you found a way to survive when you felt unseen and unsafe. That strategy helped you once. It just does not help you feel whole now.

Some gentle steps:

- Notice when you slip into performance mode. Just notice, without attacking yourself.

- Ask quietly: “What am I afraid people will see if I don’t impress them?”

- Offer yourself kindness: “It makes sense I learned to do this. I was trying to feel safe.”

- Try tiny moments of honesty: share something small and real with someone you trust, and see that you are not rejected for it.

The goal is not to crush the part that shows off. The goal is to understand it, thank it for trying to protect you, and slowly let your real self step forward more often.

Growing beyond the need to show off

As you build self-respect and self-trust, the need to exaggerate can soften. You may:

- Feel less pressure to impress

- Find comfort in being ordinary and real

- Discover that people can like you for your true self, not your performance

Showing off is not a sign of a bad person. It is usually a sign of an unmet need. When that need for safety, care, and acceptance begins to be met, especially by yourself, so the mask can gently loosen, and the shame-faced self can start to feel human again.

The hidden hole behind the persona

Many famous people who seem larger than life on stage or on screen are, inside, carrying a deep sense of emptiness and not-enoughness. Their “show” often becomes the only place they feel allowed to exist, so they pour all of their hurt into something the world will applaud.

Research on celebrities and mental health shows that fame often sits on top of old wounds, like childhood neglect, trauma, or early emotional loss. These early hurts can leave a person with a shaky sense of who they are and whether they matter, even if the world later calls them a “star.”

The role or persona that society loves then becomes a kind of mask: the funny one, the wild one, the tortured genius, the tragic singer. The more the world demands that mask; night after night, tour after tour; the less space there is for the frightened, lonely human underneath.

Robin Williams: joy on the outside, pain underneath

Robin Williams made millions of people laugh with huge, bright energy, yet close friends knew he lived with long-term depression and addiction struggles. His public persona was fast, manic, generous and sparkling; it became what people expected from him, everywhere he went.

Behind that, he wrestled with:

- Severe depression and episodes of addiction relapse

- Health problems, including heart surgery and, later, undiagnosed Lewy body dementia, which can worsen mood and thinking and raise suicide risk

Work roles and public demand kept asking for “more Robin,” even as his inner resources were wearing thin. In the end, he died by suicide, and only afterwards did the full picture of his neurological illness and mental suffering become clear. The world had loved his expression of energy and pain, but the inner hole was never fully healed.

Amy Winehouse: pain turned into a product

Amy Winehouse’s voice and songs carried raw heartbreak that resonated with millions. Yet her life was shadowed by addiction, bulimia, and mood problems, made worse by the pressure and gaze of fame. Her “troubled” persona, her drinking, chaos, saying “no” to rehab, was folded into her public image and even her biggest hit, so the world consumed her pain as entertainment.

Underneath were:

- Long-term struggles with alcohol and drugs

- Eating disorder and depression

- Environments that normalised heavy substance use and self-destruction

The industry and fans kept wanting more performances, even as it became clear she was unwell. She died at 27 from alcohol poisoning, her inner emptiness and self-harm never truly addressed in a way that could stick.

The niche that feeds the wound

Studies on rock and pop stars show that those with difficult childhoods are more likely to engage in health-damaging behaviour once they become famous, especially in scenes where drugs and risk are everywhere. Fame can give them a niche where their pain is “useful”:

- The sad songs sell.

- The wild behaviour gets clicks.

- The “tortured artist” narrative is romanticised.

The person’s wound becomes part of the brand. Their emptiness is dressed up and sold back to the public, sometimes multiple times a day in shows, interviews, or social media content. But because the applause is for the mask, not the real self, the hole inside often feels even bigger and more unreachable.

What often happens in the end

Without deep, ongoing support and a space where they can be fully human, not just “on”, and many such people end up burned out, addicted, or suicidal. There is evidence that celebrity suicides and overdoses are not rare, and that their deaths can even trigger more distress and copycat behaviour in the wider public.

The pattern is heartbreakingly common:

- A painful early life

- A talent that becomes the only safe outlet for that pain

- Fame that demands the performance of that pain on repeat

- Increasing isolation, shame, and fear of being “found out” as empty or broken

- Collapse through addiction, mental illness, or suicide when the mask can no longer be held up

Holding these stories with care

It is important to see these people not as failed idols, but as humans whose suffering was never fully met. Their “showing off” was often a desperate, creative attempt to turn inner chaos into something lovable, acceptable, and paid for. Society liked the product, but often failed the person.

If anything, their stories invite a gentler view of our own masks: the parts of us that perform, please, exaggerate, or overwork to avoid that “rock bottom” feeling of not being enough. Their lives can remind us that what saves us is not more applause, but places and relationships where we can drop the act, be seen as we are, and begin to heal the hole instead of decorating it.

Being odd, funny, self‑mocking, and sharply honest about your own flaws can be a sign of real wisdom, not weakness. Many skilled comedians, writers, and public figures use humour and self‑defacing honesty as a way to tell the truth safely and to connect with others on a deep level.

When it comes from a grounded place, this kind of humour shows:

- insight: seeing human weakness clearly, starting with your own.

- humility: not needing to pretend you are above mistakes.

- Courage: being willing to be the first one in the room to say, “Yes, I’m a mess too.”

The key difference is whether the joke is a shield for self-hate, or a soft, knowing smile at being human. In the first case, it eats you from the inside. In the second, it frees both you and the people listening. Wise “odd” people can use this style to deflate Ego, invite others out of shame, and make big truths easier to bear.

Further Reading

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3533086/

- https://www.qeios.com/read/M9TP1U/pdf

- https://www.latimes.com/entertainment/movies/la-et-mn-robin-williams-last-days-20140813-story.html

- https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20140814-robin-williams-art-out-of-agony

- https://acl.gov/news-and-events/acl-blog/robin-williams-raising-awareness-about-depression

- https://www.newleafrecovery.co.uk/robin-williams-his-story-through-addiction-depression/

- https://www.banburylodge.com/blog/celebrity/how-amy-winehouses-bulimia-battle-can-encourage-seeking-help/

- https://www.volunteerfdip.org/what-celebrities-death-by-mental-health-issues-tells-us

- https://abcnews.go.com/Health/w_MindBodyNews/amy-winehouse-career-shadowed-addiction/story?id=14145112

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amy_Winehouse

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2652970/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10278356/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6849446/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7451094/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1121899/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6549453/

- https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/blog/am-i-dying/202507/how-to-cope-when-your-childhood-heroes-die

- https://vaknin-talks.com/transcripts/Why_Celebrities_Die_Young_TalkTV_with_Trisha_Goddard/

- https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-lists/celebrity-deaths-that-changed-music-history-gone-too-soon-195319/

- https://www.imdb.com/list/ls057855859/

- https://www.nickiswift.com/1837941/teen-show-actor-deaths/

- https://innerliferecovery.com/addiction-story-amy-whinehouse-what-happened/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PpN_8BDT8zM

- https://filmstories.co.uk/features/mental-health-matters-when-someone-famous-passes/

- https://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2014/08/robin-williams-depression

- https://www.facebook.com/groups/1438524067028265/posts/1771526557061346/

- https://drlindajohnston.com/robin-williams-and-depression/

- https://news.northeastern.edu/2024/05/16/amy-winehouse-biopic-back-to-black/

0 Comments