“Organisational Behaviour” by Grace Prerana is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Organisational Behaviour

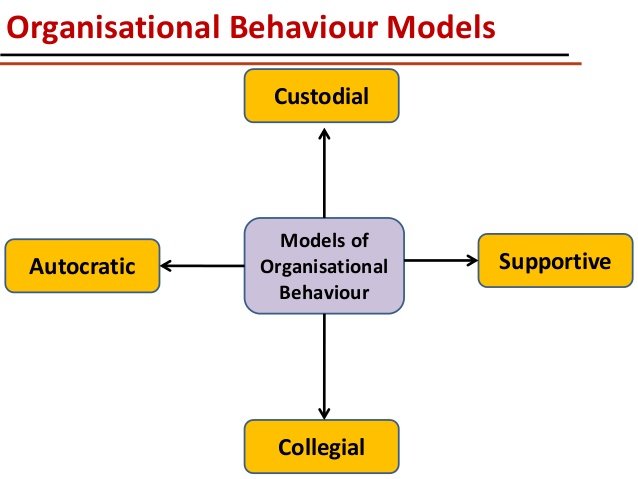

Organisational behaviour is the study of human behaviour within organisations, focusing on how individual, group, and structural factors affect performance and dynamics. It uses insights from psychology, sociology, and management to understand how to improve productivity, leadership, and teamwork. Key elements include the people (employees and their interactions), the structure (hierarchies, roles, and workflows), the technology (tools and systems), and the external environment.

Core concepts

Individual level: Examines individual attitudes, personality, motivation, and job satisfaction.

Group level: Explores team dynamics, communication, conflict, and leadership.

Organisational level: Analyses the impact of Organisational structure, culture, and change management.

Key elements

People: The individuals who make up an organisation, their behaviour, and interactions.

Structure: The formal layout of roles, hierarchies, and workflows, which influences how people interact and make decisions.

Technology: The tools and systems used, which affect productivity, performance, and employee engagement.

Environment: The external factors (like market trends) and internal culture that influence the organisation.

Why it is important

Improves performance: Understanding how behaviours affect performance helps leaders and managers improve productivity.

Enhances leadership: Leaders can gain self-awareness and insight into how their behaviour impacts others.

Boosts teamwork and communication: OB provides tools to improve communication and strengthen teamwork.

Facilitates change: It helps organisations navigate change by addressing resistance and adjusting management approaches, policies, and culture.

Increases employee engagement: A better understanding of employee needs and motivations can lead to higher engagement and a more sustainable workforce.

Organisational Incongruence

While there are many theories that help explain why organisational incongruence is so widespread, yet, for the most part, is also mostly, overlooked, and tends to be regarded as some “normalised” trend.

Here is a summary list of those theories.

Path Dependence Theory

Path dependence explains institutional inertia through self-reinforcing mechanisms making changes irreversible after early contingencies. 3-phase model (Sydow et al.): Pre-formation (contingent choices), Formation (increasing returns, feedback loops lock path), Lock-in (dysfunctional rigidity resists reversion).

Historical Institutionalism

Historical institutionalism (HI) is an institutionalist social science approach that emphasizes how timing, sequences and path dependence affect institutions, and shape social, political, economic behaviour and change.

Unlike functionalist theories and some rational choice approaches, historical institutionalism tends to emphasize that many outcomes are possible, small events and flukes can have large consequences, actions are hard to reverse once they take place, and that outcomes may be inefficient.

A critical juncture may set in motion events that are hard to reverse, because of issues related to path dependency.[Historical institutionalists tend to focus on history (longer temporal horizons) to understand why specific events happen.

Organisational Path Dependence Framework

The Organisational Path Dependence Framework explains how an organisation’s past decisions, investments, and routines create a self-reinforcing cycle that makes it difficult to change course, even when new circumstances make older methods less optimal. This framework, which is often viewed as a process with distinct stages like preformation, formation, and lock-in, uses concepts like self-reinforcing mechanisms, inertia, and network effects to show how history constrains an organisation’s future actions.

Core concepts

Past events shape the future: Similar to how the QWERTY keyboard’s layout became dominant due to early technological limitations, organisations can get locked into past choices that are no longer the best option.

Self-reinforcing mechanisms: Once a path is chosen, previous investments, established routines, and institutional norms create a feedback loop that reinforces the existing path and makes it harder to deviate.

Inertia: This refers to an organisation’s resistance to internal change, especially when faced with external shifts, and is a key outcome of path dependence.

Lock-in: This is the final stage where the organisation is “locked” into a particular path, and changing course becomes extremely difficult or even impossible.

Network effects: In some cases, a technology or strategy gains value as more people use it (like a popular software platform), which further reinforces its dominance and creates a barrier to entry for alternatives.

Functional fixity: A mental map of how something works, based on the past, can make it difficult to see or adopt new perceptions of the same technology.

Stages of path dependence

Preformation: An initial decision or event occurs.

Formation: The initial path starts to gain traction and becomes more established.

Lock-in Phase: The path becomes dominant, and the organisation is largely unable to change course.

Implications

For management: The framework helps managers understand why their organisation might be resistant to change and provides a model for managing and potentially breaking out of existing paths.

For research: It offers a way to analyse how history matters in organisations and is used to study changes in various industries, from technology to healthcare.

For strategy: Understanding path dependence is crucial for strategic planning, as past decisions can create powerful constraints on future actions and opportunities.

Policy Failure Frameworks

Policy failure can be understood through frameworks that analyse reasons for failure, such as issues with policy design, flawed implementation, or unforeseen external factors like bad luck.

Other frameworks focus on the interaction between policy content (the “what” and “how”) and the implementation context (social, political, economic factors), while some analyse failure across the policy cycle from agenda setting to evaluation. Common metrics for policy failure include not achieving original goals, failing to benefit the target group, or a lack of support from stakeholders.

Frameworks based on root causes

Bad policy, bad implementation, or bad luck: This is a fundamental framework categorizing failure based on its source.

Bad policy: Poorly designed policies with unclear goals or unintended consequences.

Bad implementation: A gap between a policy’s design and its execution, where what works in theory isn’t delivered in practice.

Bad luck: Unexpected external events like a pandemic or natural disaster that derail a policy’s success.

Frameworks based on the policy cycle

These frameworks view failure as a potential outcome at each stage of the policymaking process.

Agenda setting: Failure can occur if the initial problem is misunderstood or the policy agenda is set with unattainable goals.

Policy formulation: Risks arise from a lack of understanding of the problem or the potential consequences of proposed solutions.

Implementation: Failure can happen after a policy is selected, due to issues with putting it into practice.

Evaluation: Risks are created by inappropriate monitoring or a failure to incorporate new knowledge into future policies.

Frameworks based on policy content and context

This approach highlights the dynamic relationship between the policy and its environment.

Policy content: The “why,” “what,” and “how” of the policy itself.

Implementation context: The surrounding social, cultural, political, and economic factors that influence how a policy is received and carried out.

Interaction: A successful framework depends on how well the policy’s content aligns with and is supported by its implementation context.

Metrics and indicators of failure

These frameworks are useful for evaluating whether a policy has failed, often used in combination with the root cause or cycle frameworks.

Failure to meet goals: The policy does not achieve its stated objectives.

Stakeholder opposition: High and sustained opposition from key groups or the general public.

Lack of support: Support for the policy remains consistently low among targeted stakeholders.

Failure to benefit: The policy does not benefit the intended target group or the benefits do not outweigh the costs.

Failure to improve: The policy does not improve the situation compared to the status quo or other jurisdictions.

Organisational Hypocrisy (Brunsson)

Organisational hypocrisy is the inconsistency between an organisation’s stated values or talk and its actual decisions and actions. This gap can arise from conflicting stakeholder demands and can lead to negative consequences like damaged employee morale, though some argue it can offer flexibility in management. A prominent example is Volkswagen’s Dieselgate scandal, where the company was caught manipulating emissions tests despite publicly promoting environmental responsibility.

Characteristics of Organisational hypocrisy

Inconsistency: It involves a disconnect between what an organisation says (talk), what it decides, and what it does (actions).

Conflicting values: organisations often face conflicting demands from various stakeholders (e.g., shareholders, employees, regulators), which can lead to hypocritical behaviour as they try to appease different groups.

Appearance vs. reality: A hypocritical organisation may try to “appear something that it is not” to maintain a positive image or legitimacy.

Examples:

Leadership: A manager states they value employee input but consistently dismisses ideas from junior staff.

Corporate behaviour: Companies that promote sustainability while their actions are environmentally damaging, such as Volkswagen’s emissions scandal.

Potential impacts

Negative consequences:

- Damaged Organisational culture and employee morale.

- Loss of trust and credibility.

- Decreased employee performance and engagement.

Potential benefits (for management):

- Provides flexibility to manage conflicting demands from different stakeholders.

- May allow for impression management to maintain public or stakeholder approval.

Signalling Theory + Goodhart’s Law

Signalling Theory and Goodhart’s Law are two distinct concepts that intersect in situations involving the use of metrics and incentives, particularly when information is asymmetric.

Signalling Theory

Signalling theory, developed primarily by economist Michael Spence, describes how one party (the sender) with private information can credibly convey that information to another party (the receiver) who is making a decision under uncertainty. The effectiveness of a signal depends on its honesty and reliability, which is often tied to its cost or difficulty to fake.

Example: In the job market, an education from a prestigious university can be a signal to employers (receivers) of a candidate’s (sender’s) intelligence, work ethic, and ability, which are otherwise unobservable qualities. The cost (tuition, effort) makes the signal credible.

Goodhart’s Law

Goodhart’s Law, named after British economist Charles Goodhart, states: “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure”. The principle suggests that once a specific metric is used for control or evaluation purposes, individuals will focus on optimizing that metric, often to the detriment of the actual, broader goal it was intended to measure.

Example: If a software team is given a target for the number of lines of code written per day, they might produce bloated or unnecessary code to hit the target, rather than focusing on quality and efficiency (the true goal).

The Intersection

The two concepts interact in situations where metrics are used as signals in the presence of information asymmetry. Goodhart’s Law essentially describes the breakdown of a signal when it is turned into a target:

Metric as a Signal: Initially, a metric might be a good, organic signal of a desired underlying quality or outcome (e.g., number of publications might signal a good scientist).

Metric as a Target: When that metric is explicitly targeted for control or reward, individuals engage in strategic behaviour to game the system (e.g., academics focus on publishing many low-impact papers rather than high-impact research).

Signal Degradation: This “gaming” devalues the metric, and it loses its original meaning and reliability as a signal of the true goal, creating a “cat-and-mouse game” between those setting the metrics and those trying to meet them.

In essence, signalling theory explains why individuals produce signals in an uncertain environment, while Goodhart’s law warns that using a single, easily manipulated proxy as the sole basis for evaluation will cause the signal’s reliability to collapse. To mitigate this, organisations are advised to use multiple, balanced metrics and qualitative assessments to maintain a holistic view of the true objectives

Epistemic Malevolence + Nudge Exploitation

“Epistemic malevolence” is the disposition to harm others by deceiving them, often by manipulating their decisions through information control. “Nudge exploitation” refers to the unethical use of “nudging” techniques (subtle changes in choice architecture) to exploit people’s cognitive biases for the benefit of the nudger, rather than the individual being nudged.

When combined, “epistemic malevolence + nudge exploitation” describes the specific, intentional use of manipulative choice architecture to deceive and harm others.

Epistemic Malevolence

Epistemic malevolence is an “epistemic vice,” which are patterns of behaviour that undermine the acquisition or sharing of knowledge. It specifically involves an intention to cause material harm to others by leading them to make poor decisions based on deception.

organisations can use two main strategies for this:

Sowing doubt: Contesting information that others already have access to (e.g., tobacco companies discrediting research that linked smoking to cancer).

Exploiting trust: Concealing, obfuscating, or falsifying information that the organisation itself controls (e.g., Volkswagen installing “defeat devices” in their diesel engines to cheat emissions tests).

Nudge Exploitation

“Nudging” generally involves altering the “choice architecture” in a way that predictably changes people’s behaviour without forbidding any options (e.g., placing healthy food at eye level in a cafeteria).

Ethical concerns arise when nudges are considered manipulative or exploitative. Nudge exploitation occurs when:

- Existing irrationality is leveraged for the nudger’s gain, not the individual’s well-being.

- Salience of facts is distorted: A nudge might make an unimportant issue seem highly relevant, or an important one disappear from the decision-making process.

- Transparency is absent: The individual is often unaware they are being influenced covertly.

The Combined Concept

The combination of “epistemic malevolence” and “nudge exploitation” represents a scenario where an actor (individual or organisation) intentionally designs an environment (choice architecture) to deceive people and manipulate their decision-making processes for the malevolent purpose of causing them harm (such as financial loss, health issues, etc.), using the subtle and often hidden methods characteristic of nudging.

Bad Norms Enforcement (Evolutionary Game Theory)

In evolutionary game theory (EGT), “bad norms” refer to collectively harmful behaviours that persist because individuals are incentivized to follow and even enforce them, often through peer punishment. This enforcement can make detrimental norms evolutionarily stable, even when better alternatives exist.

Mechanisms in EGT

Peer Punishment: The primary mechanism is the willingness of individuals to punish norm-violators, even at a personal cost (altruistic punishment). While this mechanism is crucial for the evolution of prosocial cooperation, it is also a general mechanism that can stabilize any norm, including those that reduce collective welfare.

Coordination Games: Societies facing high levels of external threat (ecological or man-made) tend to develop “tighter” norms with high punishment for deviation, as coordination is vital for survival. This societal tightness creates an environment resistant to change, even if a new norm would be more beneficial.

Reputation and Indirect Reciprocity: Norms often rely on reputation systems (e.g., social standing). Certain judgment norms, such as “Stern Judging,” which assign a bad reputation to those who cooperate with individuals of already bad standing, can help a norm spread and become dominant in a population. This can reinforce harmful norms if the initial interpretation of “bad” behaviour is skewed.

Cultural Inertia: Established norms create cultural inertia, making populations reluctant to try out new behaviours. This “stickiness” means that once a bad norm becomes established, it can remain stable and resist change even when individuals recognize its negative impact.

Bi-stability: The presence of injunctive social norms can create bi-stability in game dynamics, meaning a population can settle on either a beneficial (e.g., all-cooperation) or a harmful (e.g., all-defection) equilibrium, depending on initial conditions.

Moral Dissonance Model (MDM)

The Moral Dissonance Model (MDM) is a framework that explains how people experience psychological distress when their behaviour clashes with their moral beliefs, a state of “moral dissonance”. It combines two key components: the “is” (an individual’s actual behaviour in a morally ambiguous situation) and the “ought” (the morally desirable behaviour). If an individual cannot resolve this dissonance, it can lead to more severe issues like moral injury.

Compensatory Belief Systems

Compensatory belief systems are cognitive strategies where individuals believe a negative behaviour can be offset by a subsequent positive one to reconcile conflicting goals. For example, someone might eat an unhealthy snack while believing they can “make up for it” by exercising later, which helps them reduce feelings of guilt and maintain a positive self-image, even if the compensatory action isn’t taken or is insufficient.

These beliefs can justify indulgent or unhealthy behaviours in the short term but are problematic if the compensating behaviour doesn’t happen or isn’t enough to balance the negative effects.

Motivational dissonance leads to endorsing organism-damaging habits (addiction cycles) as healthy adaptations. Pleasure/reward reinforces acceptance; long-term damage ignored. Social enforcement: Collective denial sustains (e.g., “moderation” of destructive behaviours).

Enactive Habit Theory + Norm Psychology

The Enactive Habit Theory is an approach in cognitive science that views habits not as rigid, automatic behaviours, but as flexible, adaptive, and self-sustaining networks of sensorimotor processes that are central to an agent’s identity and sense-making. This framework is then integrated with Norm Psychology to explain how individual habits are shaped by, and in turn shape, social and cultural norms, forming a continuous spectrum of normativity from basic biological needs to complex social interactions.

Psychoanalytic Organisational Defence Mechanisms

Psychoanalytic Organisational defence mechanisms are unconscious psychological strategies used by individuals within a group to protect the self and the collective from anxiety and internal conflict. These mechanisms, a concept originating from Sigmund Freud and his daughter Anna Freud, include denial, projection, and displacement, and are used by the “Ego” to mediate between the “id” and “superego”. They can manifest as primitive or mature strategies, with an over-reliance on immature defences sometimes indicating a need for psychodynamic therapy to improve self-awareness

Lacanian Organisational Identity

Lack/struggle mirrored: Individual Symbolic failures (impossible wholeness), lead to Organisational jouissance in repetition of harm (death drive rituals). Self-sabotage → “resilience virtue” via fantasy of completeness.

Organisational jouissance refers to a paradoxical form of enjoyment within organisations, often derived from a persistent, unsatisfying struggle to achieve a promised ideal or to overcome a fundamental lack.

It can manifest as a compulsive drive to organize, a thrill in procrastinating until the last minute, or the excessive pursuit of perfection, where the struggle itself becomes a source of pleasure despite the accompanying stress. This concept uses Jacques Lacan’s psychoanalytic idea of jouissance to analyse how organisations and their members find a form of satisfaction in the very failure to reach their goals.

Systems Psychodynamics (Tavistock)

Systems psychodynamics is a field of study that combines psychoanalytic theories with systems thinking to understand human behaviour in social and Organisational contexts. It argues that individuals bring their unconscious motivations, fears, and conflicts. These are shaped by early experiences, and are transferred into organisations, influencing how they interact with each other and the system itself. By integrating psychological forces with the structure and task of the organisation, systems psychodynamics aims to provide a holistic approach to analysing and addressing social and Organisational problems.

“Micro-macro mirroring” describes a concept where small-scale patterns or behaviours reflect larger, macro-scale ones, and vice versa, as seen in philosophy, art, and science. It can also refer to a specific scientific and engineering technique used in fields like material science and engineering, where the micro-level properties and behaviour of a material are used to model and predict its macro-level performance. The core idea is that the microscopic and macroscopic worlds are interconnected and often mirror each other,

Further Reading

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1008071/pdf

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.572478/pdf

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10040702/

https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/1e533178b29dd1339c77186a25248b4ab0b1e2d5

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/bridging-psychoanalytic-theory-Organisational-culture-anderson-pvlpf

https://repository.londonmet.ac.uk/1535/1/HunterMichelle_Thesis_Final.pdf

https://repository.essex.ac.uk/4085/1/9781906948108LacanAndorganisation.pdf

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0065260106380045

https://www.matec-conferences.org/articles/matecconf/pdf/2016/36/matecconf_tpacee2016_07021.pdf

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9908574/

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.595995/pdf

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8005544/

https://journals.aom.org/doi/10.5465/amr.2006.20208687

https://www.uop.edu.pk/ocontents/Change%20Management%20Book.pdf

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/ijmr.12372

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/21582440221079891

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7550469/

https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10110863/1/Glasspoole-Bird_10110863_Thesis_sig_removed.pdf

https://www.yorku.ca/dcarveth/existentialism.pdf

https://repository.tavistockandportman.ac.uk/2754/1/Hodgson%20-%20Emotional.pdf

https://us.sagepub.com/sites/default/files/upm-binaries/35408_Chapter1.pdf

https://academic.oup.com/jcmc/article-pdf/28/4/zmad023/50739520/zmad023.pdf

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9951153/

https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0749597823000195

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11591133/

https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/200834/1/Brave_New_Nudge_Accepted_Version.pdf

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6972625/

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9746791/

https://arxiv.org/pdf/2406.17160.pdf

https://arxiv.org/pdf/2405.08832.pdf

https://www.theminimalists.com/podcast/

https://oro.open.ac.uk/52371/1/equalbite.pdf

https://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/id/eprint/15125/1/681735.pdf

https://pure.uva.nl/ws/files/239424362/book_9780262380768.pdf

https://library.oapen.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/98766/9783111397719.pdf

https://arxiv.org/pdf/1804.06196.pdf

https://jorgdesign.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s41469-017-0014-1

0 Comments