“Two step flow of communication” by Nisimlevi is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

The Two-Step Flow Model of Communication

Conceptual Overview

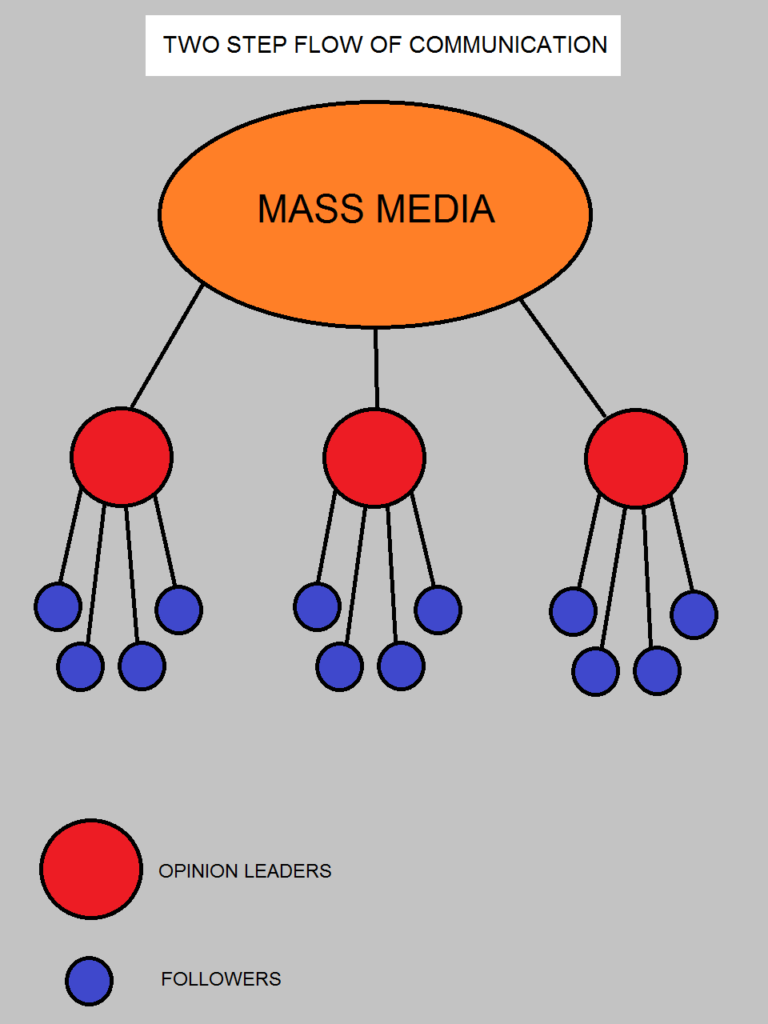

The two-step flow model of communication, formulated by Katz and Lazarsfeld (1955), proposes that the influence of mass media on the public is not direct, immediate, or uniform. Instead, media messages travel through a mediating social layer before they shape public understanding or behaviour.

According to the model, media content initially reaches a subgroup of individuals known as opinion leaders (influencers, recognised authorities, etc.). These are people who are more exposed to media, more interested in particular topics, and more socially active in discussing those topics. Opinion leaders interpret, evaluate, and selectively transmit the information to others within their interpersonal networks. As a result, the general population receives media messages filtered through the perspectives and judgments of these intermediaries.

This model stands in deliberate contrast to earlier “direct effects” frameworks – most notably the hypodermic needle or magic bullet theory – which assumed that mass media operated as an all-powerful, uniform force injecting messages straight into passive audiences. Katz and Lazarsfeld instead emphasised that individuals’ responses to media are shaped by interpersonal relationships, contextual meaning-making, and the uneven distribution of social influence.

The two-step flow framework therefore reframes media influence as socially mediated, highlighting that communication is embedded within networks of trust, authority, and everyday discourse. In doing so, it established one of the earliest systematic arguments for audience agency and selective interpretation, foundational to modern communication theory.

Precise Definition of the Two-Step Flow Model

The two-step flow model of communication is a theory of mediated influence which proposes that mass media messages do not reach the public directly. Instead:

Media > Opinion Leaders: Information is first received by a relatively small group of socially influential individuals; opinion leaders, who are more attentive to media and more engaged with specific topics.

Opinion Leaders > Wider Population: These individuals then interpret, evaluate, and relay the information to others within their interpersonal networks, shaping how the broader audience understands and responds to the content.

Thus, media influence is indirect and socially filtered, operating through interpersonal communication rather than uniform exposure (Katz & Lazarsfeld, 1955).

Empirical Foundation: The People’s Choice (1944)

The model is grounded in data from The People’s Choice study (Lazarsfeld, Berelson & Gaudet, 1944), a longitudinal investigation into U.S. voting behaviour during the 1940 presidential election.

Key findings included:

Media rarely changed attitudes directly: Participants reported that media exposure seldom shifted their political preferences.

Interpersonal influence was decisive: Voters frequently cited conversations with influential acquaintances as the source of changes or reinforcement in their opinions.

Opinion leaders were distinct: Opinion leaders were more:

- politically interested

- media-attentive

- socially connected

This demonstrated that individuals differ in their likelihood of receiving, interpreting, and sharing media messages, and that these differences create a hierarchical flow of communication.

The empirical evidence explicitly contradicted assumptions of direct, homogeneous media effects and established interpersonal influence as a major factor in public opinion formation.

Mechanisms of Influence and Real-World Examples

Core Mechanisms

Selective Attention: Opinion leaders consume more media within their domain of interest, giving them disproportionate exposure to relevant information.

Interpretation and Framing: They evaluate messages through their own values, expertise, and social roles, thereby reshaping how information is later communicated.

Social Credibility: People place greater trust in advice from individuals they know and respect than from impersonal media organisations.

Network Diffusion: Information spreads interpersonally, via conversations, recommendations, or social participation, not simply via broadcast.

Real-world Examples

Health Behaviour: Public responses to vaccination campaigns often depend on local medical figures, teachers, or community leaders who interpret official messages. Studies repeatedly show that individuals rely more on interpersonal reassurance than on direct government communication.

Consumer Influence: Product adoption, especially in fashion or technology, often begins with small groups of early adopters whose recommendations shape broader consumer trends.

Politics: Political messages may saturate the media environment, but many voters form opinions after discussing the issues with:

- politically active friends

- workplace influencers

- social group leaders

This mirrors the core dynamic described in The People’s Choice.

Contemporary Relevance

Although formulated in the mid-20th century, the two-step flow model remains highly relevant, especially in digital environments.

Social Media as a Modern Two-Step System: Platforms like YouTube, Instagram, TikTok, and Twitter amplify the role of influencers – the digital equivalent of opinion leaders, they:

- curate information

- interpret events

- guide the perspectives of large audiences

This parallels the model almost exactly.

Fragmented Media and Micro-Opinion Leaders: Online communities create specialised opinion leaders within niches (e.g., gaming, fitness, science communication).

Algorithmic Amplification: Algorithms tend to elevate:

- charismatic communicators

- individuals with strong engagement metrics

These individuals then mediate mass information in ways that shape audience beliefs.

Decline of the “hypodermic needle” assumption: Modern communication research overwhelmingly recognises that audiences are active, selective, and influenced through social networks, not passive recipients of direct messaging.

The two-step model anticipated this shift decades before the rise of digital media.

Sources: Two-Step Flow Model & Direct Effects Models

Two-Step Flow / Interpersonal Influence

Katz, E. & Lazarsfeld, P. F. (1955) Personal Influence: The Part Played by People in the Flow of Mass Communications. New York: Free Press.

– Foundational text formalising the two-step flow model.

Lazarsfeld, P. F., Berelson, B. & Gaudet, H. (1944) The People’s Choice: How the Voter Makes Up His Mind in a Presidential Campaign. New York: Columbia University Press.

– Empirical study on which the theory is based.

Katz, E. (1957) “The Two-Step Flow of Communication: An Up-to-Date Report on an Hypothesis.” Public Opinion Quarterly, 21(1), pp. 61–78.

– Important clarification and refinement of the theory.

Katz, E. & Menzel, H. (1959) “Patterns of Influence in a Communication Situation.” Public Opinion Quarterly, 23(1), pp. 37–56.

– Additional empirical work on opinion leadership.

Hypodermic Needle / Direct Effects Theory

The “hypodermic needle” (also called “magic bullet”) model is often discussed as a historical simplification rather than a fully explicit theory, but it is associated with early mass communication assumptions.

Lasswell, H. D. (1927) “The Theory of Political Propaganda.” American Political Science Review, 21(3), pp. 627–631.

– Early articulation of strong, uniform media effects.

Lasswell, H. D. (1948) The Structure and Function of Communication in Society.

– Classical model emphasising powerful effects of symbolic communication.

Hovland, C. I. & Weiss, W. (1951) “The Influence of Source Credibility on Communication Effectiveness.” Public Opinion Quarterly, 15(4), pp. 635–650.

– Shows strong effects under controlled conditions, often cited when discussing direct effects.

Wright, C. R. (1959) Mass Communication: A Sociological perspective.

– One of the texts that explicitly debates strong vs. weak media effects.

General & Contemporary Overviews

McQuail, D. (2010) McQuail’s Mass Communication Theory. London: Sage.

– Standard overview of media effects models including strong, weak, and networked theories.

Berger, C. R. & Chaffee, S. H. (1987) Handbook of Communication Science.

– Comprehensive treatment of media effects research.

Sunstein, C. R. (2017) #Republic: Divided Democracy in the Age of Social Media.

– Useful for connecting two-step flow to influencer dynamics today.

0 Comments