cognitive distortions refer to irrational or biased ways of thinking that can negatively affect our emotions and behaviours. These distortions often lead to a distorted view of reality and can contribute to issues such as anxiety, depression, and other mental health conditions. They can distort a person’s perception of themselves, others, and the world around them.

Introduction to cognitive Distortions

Cognitive distortions were first introduced by the psychiatrist Aaron T. Beck in the 1960s, a key figure in the development of cognitive therapy. Beck noticed that individuals with depression often engaged in distorted thinking patterns that exacerbated their negative emotions. These cognitive distortions can be considered automatic, habitual thoughts that arise in response to challenging situations.

Cognitive distortions are widely used in the field of cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT), where identifying and challenging them is a central therapeutic technique. By recognizing these distortions, individuals can begin to reframe their thoughts and develop healthier patterns of thinking, leading to improved mental health and emotional well-being.

How Cognitive Distortions Come About

Cognitive distortions can emerge from various factors, including past traumatic experiences, learned behaviours, cultural influences, and negative reinforcement. Early life experiences, especially those involving critical or neglectful caregivers, may shape how individuals view themselves and the world. Additionally, constant exposure to stress, anxiety, or depression can contribute to the reinforcement of these patterns of thinking.

For example, someone with a history of being criticized might begin to internalize a belief that they are fundamentally flawed or worthless, which leads to distorted thoughts like “I’m a failure” or “Nothing I do is good enough.” Over time, these thought patterns become ingrained, affecting the person’s self-esteem and how they respond to life’s challenges.

Impacts of Cognitive Distortions

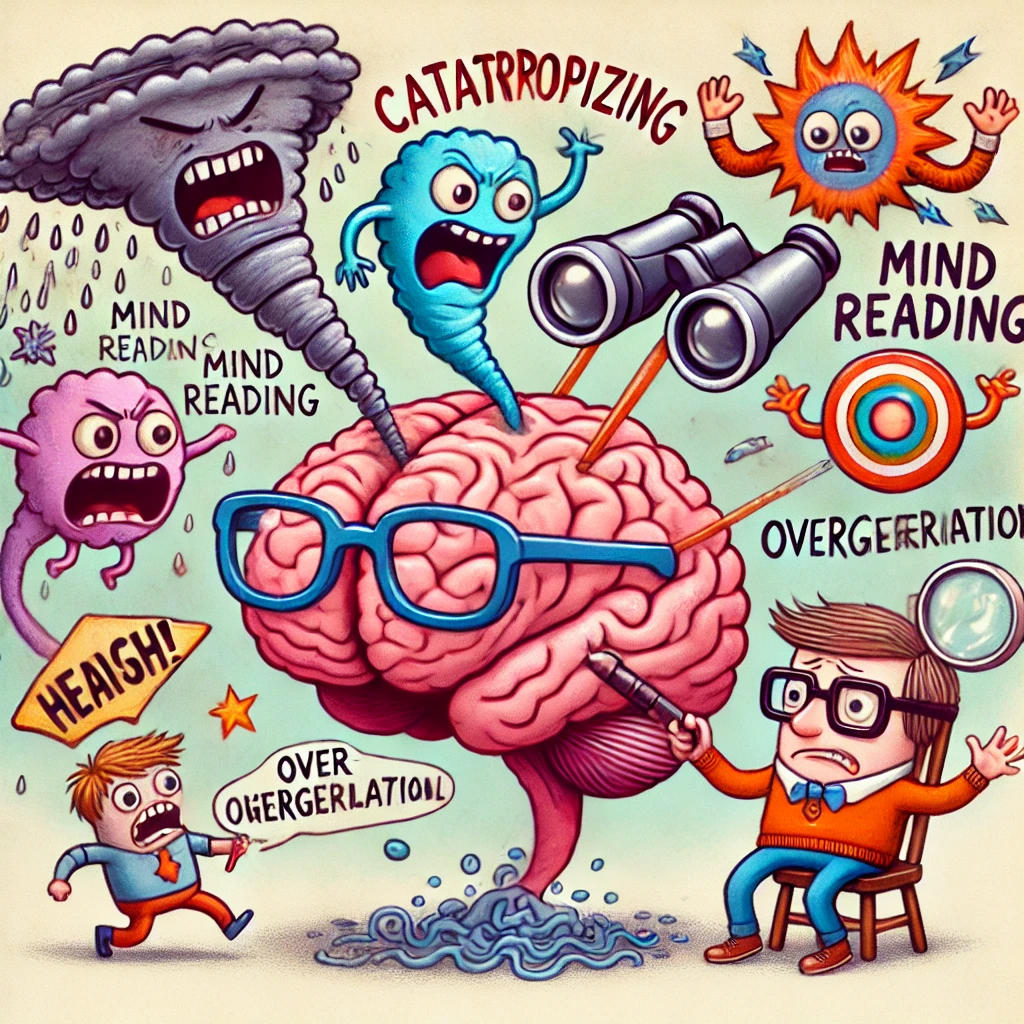

Cognitive distortions can have a profound impact on emotional and psychological well-being. These distorted thoughts can lead to feelings of hopelessness, worthlessness, anxiety, and depression. They may also interfere with the ability to engage in healthy problem-solving or make balanced decisions. Some common cognitive distortions include:

- All-or-Nothing Thinking: Seeing things as black or white, without considering any middle ground.

- Catastrophizing: Expecting the worst possible outcome or blowing things out of proportion.

- Overgeneralization: Making sweeping conclusions based on a single incident or piece of evidence.

- Personalization: Blaming oneself for events outside one’s control.

- Mind Reading: Believing you know what others are thinking, often assuming they have negative thoughts about you.

When these cognitive distortions are not addressed, they can contribute to chronic mental health problems. For example, persistent catastrophizing can lead to heightened anxiety, while overgeneralization can perpetuate feelings of inadequacy or failure.

How Cognitive Distortions Can Be Diminished or Removed

Therapeutic interventions, especially those from cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT), are often used to identify and challenge cognitive distortions. The goal is to help individuals become more aware of these automatic thoughts and recognize how they contribute to emotional distress.

Some of the key techniques for diminishing cognitive distortions include:

- Cognitive Restructuring: This technique involves identifying negative thought patterns and replacing them with more balanced and realistic thoughts. For example, changing “I always fail” to “Sometimes I succeed, and sometimes I fail, but both are part of life.”

- Mindfulness: Practicing mindfulness can help individuals observe their thoughts without judgment, creating distance from distorted thinking.

- Behavioural Experiments: These experiments allow individuals to test the validity of their distorted thoughts. For example, someone who believes they are always rejected by others might test this by engaging in small social situations and observing the outcomes.

- Problem-Solving: This involves helping individuals break down overwhelming situations into manageable parts, which reduces the impact of distorted thinking and facilitates more effective responses.

- Journaling and Thought Record Sheets: These tools can help individuals track their automatic thoughts and gain insight into their patterns, which can be useful for later challenging them.

Consequences of Leaving Cognitive Distortions Unchallenged

If cognitive distortions are left to build up without intervention, they can significantly impact mental health and quality of life. Over time, they may become more entrenched, reinforcing negative emotional patterns and maladaptive behaviours. This can lead to:

- Chronic Anxiety or Depression: Constant exposure to distorted thinking can heighten feelings of fear, helplessness, and sadness.

- Reduced Self-Esteem: Persistent negative self-talk can erode an individual’s sense of self-worth, making it more difficult to achieve personal goals.

- Social Isolation: Cognitive distortions such as mind reading (believing others are thinking negatively of you) can lead to social withdrawal, creating further feelings of loneliness and isolation.

- Ineffective Coping: Without challenging these distortions, individuals may rely on unhealthy coping strategies, such as avoidance or substance use, which only perpetuate the cycle of distress.

Cognitive distortions are irrational thought patterns that contribute to emotional difficulties and mental health issues. They can arise from a variety of sources, including past experiences and learned behaviours, and can lead to feelings of anxiety, depression, and poor self-esteem. However, therapeutic techniques like cognitive restructuring, mindfulness, and behavioural experiments can help challenge and diminish these distortions. Left unchecked, cognitive distortions can build up over time, exacerbating mental health problems and leading to a negative cycle. By addressing these distortions, individuals can begin to heal and cultivate healthier, more adaptive ways of thinking.

The “I’m Not OK, You’re Not OK” Model in Therapy

- Introduction to Transactional Analysis: Eric Berne’s I’m OK, You’re OK theory introduces four basic life positions: “I’m OK, You’re OK” (healthy, positive relationships), “I’m OK, You’re Not OK” (superiority), “I’m Not OK, You’re OK” (submissiveness), and “I’m Not OK, You’re Not OK” (paranoia, hopelessness). This framework helps to understand how individuals approach relationships and communication patterns.

- Depression and “I’m Not OK, You’re Not OK”: Many individuals with depression may present with the belief that they are “not OK” and that others are similarly “not OK.” This often leads to a sense of hopelessness and a lack of trust in the therapeutic process. They might come into therapy believing they cannot be helped and may even test the therapist by resisting suggestions with responses like “Yes, but…” or “I’ve tried that, and it didn’t work.”

- Cognitive Distortions at Play: Cognitive distortions such as overgeneralization (“Nothing will ever work for me”), catastrophizing (“Therapy won’t make any difference”), and personalization (“The therapist won’t be able to help me because I’m too broken”) could all play a significant role in maintaining this worldview.

- Therapeutic Dynamics: This mindset can create a challenging dynamic in therapy. The therapist may need to help the client see that their belief system (i.e., the idea that nothing will work) is a cognitive distortion, rather than an objective reality.

- Therapeutic Response: In such cases, the therapist may use techniques like cognitive reframing or Socratic questioning to gently challenge these distortions. Over time, by addressing these cognitive distortions, the therapist can help the client shift toward a more realistic view of themselves and their relationships, gradually moving towards an I’m OK, You’re OK position.

The Role of Cognitive Distortions in Relationship Dynamics

- Cognitive distortions are often central to how individuals perceive and react to others. For example, people with depression might engage in mind reading, believing that others are critical of them, or use labelling to define others in negative ways, leading to relationship problems. These distortions can also interact with the therapist-client dynamic.

- Therapist’s Role: The therapist must maintain a strong, supportive, and non-judgmental stance, while actively addressing and reframing the client’s cognitive distortions. This often involves:

- Normalizing the Client’s Experience: Acknowledging that many people experience these types of thoughts, while helping the client understand that these thoughts are distortions, not objective truths.

- Building Trust: Gently challenging the “I’m not OK, you’re not OK” stance, the therapist can help the client reframe their perspective on both themselves and their therapist, working toward a more balanced and trusting relationship.

How Cognitive Distortions Affect the Progression of Therapy

- Self-Sabotage: Clients who internalize distorted thinking patterns might unwittingly sabotage their own progress. This is often seen when they expect failure from the start and self-fulfil the prophecy. When they resist or reject suggestions, it can slow down or halt therapeutic progress.

- Example: A client who continuously says, “I’ve tried that, it didn’t work,” may be resisting growth due to deeply ingrained cognitive distortions that have led them to believe that change is impossible. A key therapeutic task is helping the client to reframe their experiences and recognize that past attempts may not have worked due to distorted thinking, not an inability to improve.

- Therapist’s Challenge: Therapists may need to balance compassion with firmness. It’s essential to validate the client’s feelings without endorsing the idea that their negative perspective is unchangeable. This creates an environment where clients can feel safe enough to confront their cognitive distortions.

Interplay with Other Behavioural Theories

- behavioural activation: In this model, therapists focus on helping clients engage in positive behaviours that are rewarding and break the cycle of inactivity associated with depression. Cognitive distortions such as all-or-nothing thinking (believing that if you can’t do something perfectly, there’s no point in trying) can make clients resistant to taking small, incremental steps toward change.

- The Role of Homework: Assignments like keeping thought diaries or engaging in certain activities may be met with resistance in clients who exhibit cognitive distortions like discounting the positive or minimizing their successes. Helping clients recognize the value of small wins can counteract these tendencies.

integration with Other Cognitive Models

- Cognitive distortions could also be examined through the lens of Albert Ellis’s Rational Emotive Behaviour Therapy (REBT), which teaches that beliefs lead to emotional consequences. If a client holds irrational beliefs about themselves (e.g., “I’m worthless”), they will likely experience emotional distress. Through REBT, clients learn to dispute and replace these irrational beliefs with more rational ones, reducing emotional turmoil.

- Cognitive-Behavioural Techniques: Many of the techniques used in CBT, like cognitive restructuring, would also be helpful in addressing the distorted thought patterns seen in the “I’m not OK” model. These techniques encourage clients to consider alternative explanations for situations that would challenge their distorted thinking.

The Danger of Leaving Cognitive Distortions Unchallenged

- Chronic Reinforcement: If the distorted thinking isn’t addressed, it can lead to chronic, pervasive beliefs that create lasting psychological issues, including social isolation, persistent depressive episodes, and difficulty forming healthy relationships. By challenging these distortions in therapy, clients can learn to develop more adaptive thinking patterns that foster positive emotional states and interpersonal connections.

- Therapeutic Setbacks: Over time, leaving cognitive distortions unchallenged can cause a sense of learned helplessness, where clients believe their situation is hopeless and beyond their control. This can lead to a worsening of symptoms and frustration, making the therapeutic process feel like a constant battle rather than a journey toward improvement.

By integrating these behavioural theories and understanding how cognitive distortions manifest in therapy, we can offer a more holistic view of how these thinking patterns impact individuals and their healing journey.

Here’s a curated list of references and links that you can use to explore the concepts we’ve discussed and to support the ideas around cognitive distortions, behavioural theories, and therapeutic techniques:

General Understanding of Cognitive Distortions:

- Aaron T. Beck’s Cognitive Therapy:

- Beck, A. T. (1976). Cognitive Therapy and the Emotional Disorders. New York: International Universities Press.

- Overview of cognitive therapy and the foundational concept of cognitive distortions. Link to source overview

- National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) – cognitive behavioural therapy:

- Information on how cognitive distortions are addressed in therapy, particularly CBT. NIMH CBT Overview

- Cognitive Distortions: The 10 Most Common Cognitive Distortions:

- A breakdown of common cognitive distortions, useful for understanding how they manifest. Psychology Tools – Cognitive Distortions

Transactional Analysis (TA) and the “I’m OK, You’re OK” Framework:

- Eric Berne’s Transactional Analysis Theory:

- Overview of the “I’m OK, You’re OK” theory and how it applies to relationships, including the “I’m Not OK, You’re Not OK” model. Transactional Analysis Basics

- Berne’s Games People Play:

- A deeper dive into how transactional analysis plays out in real-world behaviour, particularly in therapy. Games People Play

Behavioural Theories and Therapeutic Techniques:

- Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy (CBT) Resources:

- Information on how CBT is used to challenge cognitive distortions and implement change. CBT Techniques Overview

- Behavioural Activation (BA) Therapy:

- A specific behavioural therapy designed to address inactivity and depressive symptoms. Behavioural Activation Overview

- Albert Ellis’s Rational Emotive Behaviour Therapy (REBT):

- Ellis’s approach to cognitive distortions and irrational beliefs. Albert Ellis Institute Overview

Mindset and the Role of Cognitive Distortions in Therapy:

- The Role of Cognitive Distortions in Depression and Anxiety:

- A look at how distorted thinking patterns contribute to emotional disorders and how they are addressed in therapy. Mind Over Mood – Cognitive Distortions

- The Impact of Cognitive Distortions on Therapy Progress:

- An article discussing how cognitive distortions can create resistance to change in therapy and how they are overcome. Therapy Progress & Cognitive Distortions

- How to Challenge Cognitive Distortions in Therapy:

- A practical guide to helping clients challenge their cognitive distortions during therapy. Challenging Cognitive Distortions

These links and references should help provide a solid foundation for your research and exploration into cognitive distortions, behavioural therapy, and their intersection in the therapeutic process.

0 Comments