Click below to listen to this article:

The human multiplicity theory

Summary

Are humans singular or plural? This question may seem paradoxical, but it is at the heart of a growing field of inquiry that challenges the conventional notion of human identity as fixed and unitary. In this thesis, I will describe my concept that humans are multiplicities, meaning that they are composed of multiple selves, identities, perspectives, and experiences that coexist and interact within a single person. I examine the theoretical and empirical foundations of this concept, as well as the supporting evidence that helps confirm this idea. I add insight as to how this concept of the human multiplicity functions in individuals, and its implications for various domains of human life, such as psychology, ethics, politics, and art. I also discuss what happens when aspects of the multiplicity becomes distorted and dissociated, and how this impacts our mental health and sense of wellbeing. I also discuss an approach to correcting and healing such dysfunctions. By doing so, I hope to shed some light on the complexity and diversity of human nature, and to invite readers to reflect on their own multiplicity.

Note: This theory represents the thinking of one person who has studied psychology extensively and has brought together several established psychological and spiritual theories, together with their own to create a cohesive theory explaining human behaviour and spirituality, this should not be seen as anything official and has not been peer-reviewed or published in any established journals.

The multiplicity concept

The term multiplicity, used here, implies that humans have the capacity to change, adapt, grow and transform in different contexts and situations, and that they can hold multiple perspectives, opinions and interests at the same time. It also recognizes that humans are influenced by various social, cultural, historical and environmental factors that shape their sense of self and their interactions with others. Multiplicity challenges the notion that there is one true or essential way of being human, and instead celebrates the diversity and richness of human potential.

The idea that humans are a multiplicity, meaning that they have different aspects or facets of their identity, personality, or self, has a long and complex history. One of the earliest sources of this idea can be traced back to Ancient Greece, where philosophers such as Plato and Aristotle proposed different models of the human soul, which consisted of rational, spirited, and appetitive parts. These parts were often in conflict with each other, and the goal of ethics was to achieve harmony among them.

Plato, in his dialogue Theaetetus, explores the nature of knowledge and its relation to perception. He uses the metaphor of a bird cage to illustrate how the mind can acquire, store, and recall different kinds of knowledge (Plato, 2016). According to Plato, the mind is like a cage that contains many birds of different sizes and colours, representing different types of knowledge. Some birds are common and easy to catch, such as the knowledge of basic facts and definitions. Others are rare and elusive, such as the knowledge of the highest forms and principles. The mind can catch these birds by using perception, memory, reasoning, and intuition.

However, the mind can also make mistakes in catching and identifying the birds, such as confusing opinion with knowledge, or mistaking appearance for reality. Therefore, Plato argues that true knowledge is not merely a matter of having many birds in the cage, but of being able to distinguish them correctly and use them appropriately.

Plato’s metaphor of the mind as a bird cage can be related to the human multiplicity theory, which proposes that human beings have multiple selves or aspects of personality that interact with each other and with the environment (Rowan, 1990).

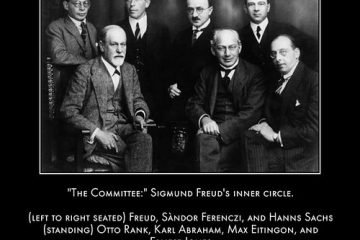

Another influential source of the idea of human multiplicity was the psychoanalytic theory of Sigmund Freud, who proposed that the human psyche was composed of three main structures: the id, the ego, and the superego. The id was the source of instinctual drives and desires, the ego was the mediator between the id and reality, and the superego was the internalized moral authority. Freud argued that these structures often clashed with each other, resulting in psychological problems such as neurosis and repression.

In the 20th century, the idea of human multiplicity was further developed by various schools of psychology, such as humanistic, existential, cognitive-behavioural, and transpersonal. These schools emphasized different aspects of human experience, such as Self-actualization, meaning-making, cognitive schemas, and spiritual dimensions. They also proposed different methods of exploring and integrating the multiple facets of human existence, such as therapy, meditation, art, and dialogue.

The idea of human multiplicity is increasingly relevant today, as it offers a rich and nuanced perspective on human nature and potential. It also challenges the notion of a fixed or singular self, and invites us to embrace the diversity and complexity of our being.

Whilst the notion of proving that humans are multiplicities has so far proven to be a challenge to science, it is, however, becoming increasingly clear that many people already accept this as a truth about themselves. In the field of mental health, there is increasing support and understanding that a great many people experience the “symptoms” of their multiple minds. For example, a huge number of people hear voices, many of which they do not associate as themselves, but another specific individual identity. We also have specifically classified mental illnesses such as dissociative identity disorder, which recognises the concept of multiple individual characters exiting within a single human body, as having multiple personalities. In addition, the field of trauma related illness is increasingly becoming confident that a common and significant response to trauma, is dissociation, resulting in multiple character aspects sharing an individual’s conscious expression.

Within this thesis, I have gathered all the supporting evidence that supports the theory that the human mind is a multiplicity, and I would suggest that based on this, there is more than enough evidence for us to make this notion one that we should hold as the most likely concept to explain the structure of the human mind.

To further underline how widespread the concept of the human multiplicity has become, let me now review the psychological concepts which support the notion of the multiple mind of the human being.

The human mind as a multiplicity

“We must accept our multiplicity, the fact that we can show up quite differently in our athletic, intellectual, sexual, spiritual—or many other—states.” – Dan Siegel

“Each of us has a variety of selves, which we draw out and put away according to the situation.” – Daniel Goleman

The human mind is a complex and fascinating phenomenon that has been studied from various perspectives and disciplines. One of the topics that has intrigued researchers and practitioners is the possibility that the human mind is not a singular entity, but a multiplicity of selves or identities that coexist in the same body. This experience of multiplicity has been conceptualized in different ways, such as dissociative identity disorder (DID), other specified dissociative disorder (OSDD), plurality, polypsychism, or simply diversity of self.

Multiplicity can be understood as a broad term that encompasses any experience of more than oneself in one’s mind or body. People who identify as multiple may have different understandings of the origin, function, and nature of their parts, alters, or selves. Some may see them as internal aspects of their own psyche, while others may see them as external entities, such as spirits, ancestors, or soul-bonds. Some may view multiplicity as a disorder, a trauma response, a disability, or a diversity. Some may experience multiplicity as distressing, impairing, or life-threatening, while others may experience it as enriching, empowering, or life-saving.

One of the psychological theories that propose that the human mind is a multiplicity is the multiple social categorization theory. This theory suggests that people can perceive themselves and others based on more than one social category, such as race, gender, age, religion, etc. For example, a person can be a black woman, a Christian, and a lawyer at the same time. These different social categories can interact and influence how people perceive themselves and others in different situations. Multiple social categorizations can have various effects on intergroup relations, such as reducing stereotyping, increasing empathy, and enhancing diversity.

Another psychological theory that implies that the human mind is a multiplicity is the cognitive theory. This theory posits that people’s thoughts and beliefs influence their emotions and behaviours. cognitive theory assumes that people can have different types of cognitions, such as schemas, automatic thoughts, irrational beliefs, etc. These cognitions can be adaptive or maladaptive, depending on how they fit with reality and how they affect one’s wellbeing.

One of the branches of cognitive theory is the theory of multiple intelligences, which proposes that human intelligence is not a single, general ability, but rather a differentiation of specific intelligences that reflect different ways of interacting with the world. According to this theory, there are at least eight types of intelligences: linguistic, logical-mathematical, spatial, bodily kinaesthetic, musical, interpersonal, intrapersonal, and naturalistic. Each person has a unique profile of strengths and weaknesses across these intelligences, and can develop them through education and training.

The theory of multiple intelligences suggests that the human mind is a multiplicity, meaning that it consists of different aspects or facets that can operate independently or in combination. This implies that people can use different intelligences to solve problems, create products, and express themselves in various domains. The theory also challenges the traditional view of intelligence as a fixed and unitary trait that can be measured by standardized tests. Instead, it proposes a more dynamic and diverse conception of intelligence that respects individual differences and cultural diversity.

The theory of multiple intelligences has been applied to various fields of education, psychology, and neuroscience, and has inspired many educators to adopt more flexible and personalized approaches to teaching and learning. However, the theory has also faced some criticism and controversy regarding its empirical validity, its definition and classification of intelligences, and its implications for educational policy and practice.

The psychodynamic theory is a psychological theory that explains the origins and development of human behaviour in terms of the dynamics of the mind, such as drives, impulses, wishes, affects, unconscious processes, conflict, and defence mechanisms (Boag, 2018). According to this theory, the human mind is a multiplicity, meaning that it consists of different parts or agencies that can have conflicting goals and motivations.

Freud (1923) proposed that the mind is divided into three main agencies: the id, the ego, and the superego. The id is the source of instinctual drives and operates on the pleasure principle, seeking immediate gratification. The ego is the rational part of the mind that operates on the reality principle, mediating between the id and the external world. The superego is the moral part of the mind that represents internalized values and ideals. The ego often has to cope with the demands of the id and the superego, which can create anxiety and guilt.

To protect itself from these negative feelings, the ego uses various defence mechanisms, such as repression, denial, projection, rationalization, etc. These defence mechanisms are unconscious mental operations that distort or deny reality to reduce psychological conflict (McLeod, 2023). The psychodynamic theory also emphasizes the importance of childhood experiences and object relations for personality development.

Object relations refer to the mental representations of oneself and others that are formed through early interactions with caregivers. These representations influence how people relate to themselves and others throughout their lives. Psychodynamic therapy aims to help people understand their unconscious dynamics and resolve their conflicts by exploring their past and present relationships and emotions (Good Therapy, n.d.).

Additionally, Carl Jung was a pioneer of the concept of the collective unconscious, which he defined as a layer of the psyche that transcends the personal and contains the archetypes, or universal symbols and patterns of human experience. Jung also proposed that the psyche consists of various complexes, or clusters of emotional and mental associations, that influence one’s behaviour and personality.

One of these complexes is the ego, which represents one’s conscious identity and sense of self. However, Jung also recognized that the ego is not the whole of the psyche, but rather a part of it, and that there are other aspects of the self that are not fully integrated or acknowledged by the ego. These include the shadow, which contains the repressed or rejected parts of oneself; the anima or animus, which represents one’s inner feminine or masculine qualities; and the self, which is the totality of the psyche and the source of individuation, or the process of becoming a unique and whole person.

Based on these ideas, it could be argued that Jung would agree with the idea that humans are a multiplicity, or a collection of different selves that coexist within one psyche. Jung believed that humans are not static or fixed entities, but rather dynamic and evolving beings who constantly interact with their inner and outer worlds.

He also suggested that humans have a potential for growth and development, and that by becoming aware of and integrating their various aspects of the self, they can achieve a higher level of consciousness and fulfilment. Jung did not see multiplicity as a sign of disorder or fragmentation, but rather as a natural and creative expression of human diversity and complexity.

Internal Family Systems Theory (IFS) is an approach to psychotherapy that views the mind as a complex system of parts, each with its own perspective, interests, and emotions. IFS suggests that humans are a multiplicity, meaning that they have multiple sub-personalities or parts that can act independently or harmonizing with each other (Schwartz, 1995). IFS combines elements from different schools of psychology, such as systems thinking and the multiplicity of the mind, and posits that each part possesses its own characteristics and perceptions (Good Therapy, 2018).

According to IFS, there are three main types of parts: exiles, managers, and firefighters. Exiles are parts that carry emotional pain or trauma from the past and are often suppressed or isolated by other parts. Managers are parts that try to control the internal and external environment to prevent exiles from being triggered. Firefighters are parts that act impulsively or destructively to distract from or numb the pain of exiles (Schwartz, 1995).

IFS aims to help clients access their core Self, which is the essence of who they are and has qualities such as compassion, curiosity, and clarity. The Self is the natural leader of the internal system and can heal the wounded parts by listening to them, understanding them, and unburdening them from their negative beliefs or emotions (Schwartz, 1995).

IFS supports the idea that humans are a multiplicity by acknowledging the diversity and complexity of the human psyche and by fostering a respectful and collaborative relationship between the Self and the parts (Life Architect, 2021).

self-transcendence theory is a perspective that proposes that human beings have the capacity to expand their self-boundaries and connect with something greater than themselves, such as other people, nature, the universe, or a divine power. According to this theory, self-transcendence can enhance wellbeing, especially in situations of adversity, loss, or life-limiting illness (Reed, 2012).

One possible implication of self-transcendence theory is that humans are a multiplicity, meaning that they are not separate or isolated entities, but rather interconnected and interdependent parts of a larger whole. This idea is consistent with some spiritual and philosophical traditions that view human nature as essentially relational and communal (Cloninger, 2004). However, this implication is not necessarily accepted by all proponents of self-transcendence theory, as some may emphasize the personal or individual aspects of self-transcendence more than the collective or universal ones.

The humanistic theory is a perspective in psychology that emphasizes the individualized qualities of optimal wellbeing and the use of creative potential to benefit others, as well as the relational conditions that promote those qualities as the outcomes of healthy development (Bland & DeRobertis, 2018).

Humanistic psychologists contend that personality formation is an ongoing process motivated by the need for relative integration, guided by intentionality, choice, the hierarchical ordering of values, and an ever-expanding conscious awareness (Bland & DeRobertis, 2018). They also employ an intersubjective, empathic approach to understand the lived experiences of individuals as active participants in the life-world, situated in sociocultural and eco-psycho-spiritual contexts (Bland & DeRobertis, 2018).

One of the implications of the humanistic theory is that the human mind is a multiplicity, meaning that it is composed of multiple aspects or dimensions that are not reducible to a single unity or essence (Bergson, 1912). Humanistic theorists say these individual subjective realities must be looked at under three simultaneous conditions: as a whole and meaningful, not broken down into small components of information that are disjointed or fragmented; as unique and not comparable to other minds or averages of groups; and as dynamic and evolving, not static or fixed (McLeod, 2023). Therefore, the humanistic theory suggests that the human mind is a multiplicity that reflects the complexity and diversity of human experience and potential.

Behavioural theory is a theory of learning that states all behaviours are learned through conditioned interaction with the environment. Behavioural theory does not focus on the internal mental processes of the mind, but rather on the observable behaviours that can be measured and modified. This theory therefore suggests that the human mind is a multiplicity of conditioned responses that are triggered by different stimuli and reinforced by consequences. According to behavioural theory, the human mind does not have a single self, but rather a collection of learned behaviours that vary depending on the situation and the history of learning.

Social cognitive theory (SCT) is a learning theory that emphasizes the role of cognitive processes, social interactions, and environmental influences on human behaviour. SCT was developed by Albert Bandura as an extension of his social learning theory, which posited that people learn new behaviours by observing and imitating others. SCT adds that people also learn from the consequences of their actions, their own expectations and beliefs, and their self-regulation skills. It argues that people are active agents who can both influence and be influenced by their environment (Bandura, 1989).

One of the key concepts of SCT is the notion of multiplicity, which refers to the idea that the human mind is not a single entity, but rather a collection of different subpersonalities or aspects that can have different goals, motivations, and perspectives. Multiplicity suggests that people can switch between different modes of thinking and behaving depending on the situation, the task, and the social context. Multiplicity also implies that people can have internal conflicts or dialogues among their subpersonalities, which can affect their decision-making and problem-solving processes (Hermans & Kempen, 1993).

SCT and multiplicity theory can help explain how people cope with complex and dynamic environments, how they adapt to changing demands and expectations, and how they develop a sense of identity and agency. SCT and multiplicity theory can also provide insights into how people can enhance their learning and performance by using various cognitive strategies, such as self-monitoring, self-evaluation, self-reinforcement, goal-setting, and self-regulation (Zimmerman & Schunk, 2001).

Evolutionary theory is the scientific framework that explains how living species, including humans, have arrived at their current biological and psychological form through a historical process of natural selection and adaptation to environmental changes (BBC, n.d.). According to evolutionary psychology, the human mind evolved to benefit the individual by enhancing their chances of survival and reproduction in various domains of life, such as social interactions, mate choice, language, memory, and consciousness (Al-Shawaf, 2021).

One of the implications of this perspective is that the human mind is not a single, unified entity, but rather a multiplicity of specialized mechanisms that operate in different contexts and for different purposes. This view is supported by evidence from neuroscience, cognitive science, and psychology that shows that the brain consists of multiple modules that can function independently or in coordination with each other, depending on the situation (Psych Central, 2021).

The concept of multiplicity also has a historical origin in the 19th century mesmerism, which revealed that some individuals could manifest different personalities or identities under hypnosis, suggesting that the self is not a fixed or coherent construct (Wikipedia, n.d.). Therefore, evolutionary theory suggests that the human mind is a multiplicity of adaptive functions that emerged from the interaction between biological and environmental factors over time.

All of these theories show that many of our greatest conceptual thinkers have concluded that the human mind is a multiplicity of discrete intelligent self-aspects, which each can have their own character, values, motivations etc.

The spiritual perspective

The idea that humans are a multiplicity has been explored from various spiritual perspectives. Some of these perspectives emphasize the unity of the human spirit, while others acknowledge the diversity and complexity of human experience. For example, Husserl (1970) proposed a phenomenological approach to the human spirit, which he defined as “the absolute flow of experiences in which all objective realities are constituted” (p. 168). He argued that the human spirit is not a substance or a thing, but a process of intentional consciousness that transcends the empirical world. Husserl also suggested that the human spirit can be understood as a multiplicity of intentional acts, each with its own meaning and direction.

Bergson (1913) also explored the notion of multiplicity in relation to the human spirit, but from a different angle. He contrasted two types of multiplicity: one that is quantitative and discrete, and one that is qualitative and continuous. The former is exemplified by spatial objects and numerical concepts, while the latter is exemplified by duration and consciousness. Bergson argued that the human spirit belongs to the second type of multiplicity, which he called “duration”. He described duration as “a succession of qualitative changes, which melt into and permeate one another, without precise outlines, without any tendency to externalize themselves in relation to one another” (p. 100). Bergson also claimed that duration is the source of creativity and freedom in human life.

Another spiritual perspective on human multiplicity comes from the psychology of religion, which studies how people relate to the sacred or transcendent in their lives. Pargament et al. (2013) defined spirituality as “the search for the sacred” (p. 23), and suggested that it can take various forms and expressions depending on the individual and the context. They also proposed a model of spiritual integration, which involves the alignment of one’s multiple aspects (e.g., beliefs, values, emotions, behaviours) with one’s sacred goals and ideals. According to this model, spiritual integration can enhance wellbeing and coping by providing coherence, direction, and meaning to one’s life.

One of the ideas that Gurdjieff taught was that human beings are not conscious of themselves and live in a state of multiplicity, meaning that they have many small “I”s that take over their centres of thought, feeling and body according to changing stimuli. He said: “Man has no individuality. He has no single, big I. Man is divided into a multiplicity of small ‘I’s, and each separate small ‘I’ can call itself by the name of the Whole” (Ouspensky, 1949, p. 60). This implies that humans do not have a consistent sense of identity or purpose, but are driven by various impulses and habits that are often contradictory and conflicting.

However, Gurdjieff also suggested that there is a possibility of developing a real I, a higher self that can unify and harmonize the different aspects of human nature. He called this process “the Work” or “the Fourth Way”, which involves working on oneself through self-observation, self-remembering, conscious suffering and intentional effort. He claimed that this way was different from the traditional paths of the fakir, the yogi and the monk, who focused on only one centre at a time. He said: “The Fourth Way is not another system of self-development, it is a way of preparing for real service” (Gurdjieff, 1973, p. 39). This means that the aim of the Work is not only personal transformation, but also serving a higher purpose that transcends one’s individuality.

There are some quotations from Gurdjieff’s writings and talks that support the idea that he supported the concept of human multiplicity and its possible resolution through the Work. For example:

“Man such as we know him, the ‘man-machine,’ the man who cannot ‘do,’ and with whom and through whom everything ‘happens,’ cannot have a permanent and single I. His I changes as quickly as his thoughts, feelings and moods, and he makes a profound mistake in considering himself always one and the same person; in reality he is always a different person, not the one he was a moment ago” (Gurdjieff, 1950, p. 59).

“Man has no permanent and unchangeable I. Every thought, every mood, every desire, every sensation, says ‘I’. And in each case it seems to be taken for granted that this I belongs to the Whole, to the whole man, and that a thought, a desire, or an aversion is expressed by this Whole” (Ouspensky, 1949, p. 59).

These are just some examples of how different spiritual perspectives can shed light on the idea that humans are a multiplicity. Each perspective offers a unique lens to understand the complexity and diversity of human experience, as well as the potential for growth and transformation. However, these perspectives are not mutually exclusive or contradictory; rather, they can complement and enrich each other by highlighting different dimensions and aspects of the human spirit.

Other multiple self theories

The multiple self theory of the mind is a psychological perspective that proposes that the human mind is not a single, unified entity, but rather a collection of different selves or subpersonalities that interact, conflict, and cooperate with each other. According to this theory, each self has its own goals, beliefs, emotions, and behaviours, and can take control of the mind at different times or situations. The multiple self theory of the mind challenges the traditional notion of a coherent and stable self-identity, and suggests that people can experience shifts and changes in their sense of self depending on which self is dominant at the moment.

One of the proponents of the multiple self theory of the mind is David Lester, who has formulated a formal subself theory of the mind with 12 postulates and 49 corollaries (see Lester, 2010). Lester argues that the multiple selves in the mind can be viewed as a small group that has its own dynamics, such as leadership, roles, norms, and communication. He also suggests that each self has a complementary counterpart in the unconscious mind that balances its traits. For example, a self that is rational and logical may have an unconscious counterpart that is intuitive and creative.

The formal subself theory of personality is a theory that proposes that the mind is composed of several subselves, each of which is a coherent system of thoughts, desires, and emotions, organized by a system principle. The concept of subselves has been used by various personality theorists, such as Jung, Berne, Maslow, and Angyal, to describe different aspects of the psyche, such as ego states, complexes, syndromes, and subsystems. The formal subself theory aims to provide a systematic and comprehensive framework for understanding the structure, development, psychopathology, and psychotherapy of the mind based on the notion of subselves. The theory consists of a series of postulates and corollaries that specify the characteristics, functions, interactions, and dynamics of subselves. The theory also has implications for various topics in psychology, such as self-complexity, multiple self-aspects, identity integration, and self-regulation.

Another advocate of the multiple self theory of the mind is John Rowan, who prefers to use the term subpersonalities. Rowan (1990) describes subpersonalities as “relatively autonomous centres of awareness” that have their own history, style, and world-view. He also distinguishes between primary subpersonalities, which are formed in childhood and are related to basic needs and emotions, and secondary subpersonalities, which are developed later in life and are related to social roles and expectations.

The multiple self theory of the mind has several implications for understanding human behaviour and personality. For instance, it can explain why people sometimes act inconsistently or contradictorily in different situations or contexts. It can also help people to recognize and integrate their various selves into a more harmonious whole, or to resolve conflicts between their selves through dialogue and negotiation. Moreover, it can provide a framework for exploring the diversity and complexity of human experience and identity.

Research on the human mind as a multiplicity

Research on multiplicity has been largely influenced by the clinical psychological perspective, which focuses on the diagnosis and treatment of Dissociative Identity Disorder and Other Specified Dissociative Disorder. These are considered to be dissociative disorders that result from severe childhood trauma and involve disruptions in memory, identity, emotion, perception, and behaviour. According to the International Society for the Study of trauma and dissociation (ISSTD), DID and OSDD are characterized by the presence of two or more distinct personality states or parts that recurrently take control of the person’s behaviour, accompanied by amnesia for important personal information that cannot be explained by ordinary forgetfulness. The ISSTD provides guidelines for the assessment and treatment of DID and OSDD, which include a phased approach that involves establishing safety and stabilization, processing traumatic memories, and integrating the parts into a cohesive sense of self (ISSTD, 2011).

However, not all people who experience multiplicity identify with the diagnostic labels of DID or OSDD, or agree with the trauma-based aetiology or the integration-oriented goal of therapy. Some people prefer to use terms such as plurality or polypsychism to describe their experience of multiplicity as a natural variation in human identity construction that does not necessarily imply pathology or impairment. Some people may embrace their multiplicity as a source of strength, creativity, or spirituality, and seek to foster cooperation and harmony among their parts rather than integration, in this case, we would suggest, that cooperation is, in fact, integration. Some people may also have different cultural or spiritual explanations for their multiplicity that do not fit within the Western linear framework of understanding the self.

Therefore, research on multiplicity needs to be more inclusive and respectful of the diversity of experiences and meanings that people who identify as multiple have. There is a need for more qualitative research that explores the lived experiences of people with multiplicity from their own perspectives and voices, rather than imposing predefined categories or assumptions on them. There is also a need for more cross-cultural and interdisciplinary research that examines how multiplicity is understood and expressed in different contexts and traditions. Furthermore, there is a need for more collaborative and participatory research that involves people with multiplicity as co-researchers and co-producers of knowledge, rather than passive subjects or objects of study.

Some examples of recent research that has adopted these approaches are:

Eve Z., & Parry S. (2021). Exploring the experiences of young people with multiplicity. Youth & Policy. https://www.youthandpolicy.org/articles/young-people-with-multiplicity/

Ribáry G., Lajtai L., Demetrovics Z., & Maráz A. (2017). Multiplicity: An explorative interview study on personal experiences of people with multiple selves. Frontiers in Psychology, 8: 943. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00943

Stocks R.J.T. (2007). Toward an inclusive model of dissociation: Exploring cultural factors in dissociation theory development (Doctoral dissertation). University of Auckland. https://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz/handle/2292/2370

In addition, there is increasing acceptance that trauma can create dissociations, which are in effect separate intellects within the brain, which we have suggested serve as confirmation for the human multiplicity theory. We can include as evidence, therefore, the scientific research which seeks to confirm this trauma-caused dissociation:

A study by Lebois et al. (2022) that identified regions within brain networks that communicate with each other when people experience different types of dissociative symptoms, such as depersonalization, derealization, and dissociative amnesia. The study suggested that dissociation common to PTSD and dissociation central to DID are each linked to unique brain signatures.

A study by Deisseroth et al. (2020) that pinpointed a brain circuitry underlying dissociative experiences in mice exposed to traumatic stress. The study indicated that activating or inhibiting this circuitry could modulate the behavioural and physiological responses to stress, such as freezing, heart rate, and blood pressure.

A study by Krause-Utz (2022) that reviewed the literature on dissociation, trauma, and BPD, and highlighted the role of traumatic stress, temperamental and neurobiological vulnerabilities, and psychosocial factors in the development of dissociation. The study also discussed the implications of dissociation for diagnosis, treatment, and research of BPD.

A study by Nickerson et al. (2022) that examined the association between dissociation after trauma and mental health outcomes in a large sample of trauma-exposed individuals. The study found that dissociation after trauma was a strong predictor of PTSD, depression, anxiety, physical pain, and social impairment, and suggested that early intervention and prevention strategies are needed for this population.

These studies seek to show that dissociation can be caused by trauma, and suggest dissociated aspects show differing neurological responses and centres of activation in the brain than the individuals’ normal self. This can help inform my concept that those dissociations are responsible for differing areas of self-regulation and control within the brain.

Other forms of evidence for the mind as a multiplicity

If there ever was a widespread human experience which provides significant evidence that the human mind is a multiplicity, then it is through the phenomena of individuals who hear voices.

Hearing voices is a phenomenon that affects a significant number of people worldwide. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), nearly 2.5 billion people, or one in four, will be living with some degree of hearing loss by 2050 (WHO, 2021). Hearing loss can impair the ability to communicate and interact with others, and may lead to social isolation, depression and reduced quality of life, and also, many deaf people hear voices.

Deaf people are not a homogeneous group when it comes to their experience of hearing voices. Some deaf people may have an inner voice that is auditory, visual, or a combination of both, depending on their hearing loss and language background. Others may have an inner hearing that is based on sign language or other visual cues. Deaf people who have voice-hallucinations as a symptom of schizophrenia may also perceive voices differently, depending on their level of language acquisition and exposure to sound (Atkinson, 2007). Research suggests that deaf people who have some experience of hearing speech may report auditory voice-hallucinations, while those who are born profoundly deaf may report non-auditory, clear, and easy to understand voices that are accompanied by sub-visual imagery of signing or lip movements (Atkinson, 2007). Deaf people who have severe language deprivation and incomplete acquisition of either speech or sign may not experience any organized voice-hallucinations at all (Atkinson, 2007). Therefore, it is important to explore how deaf people ‘hear’ voice-hallucinations in relation to their individual characteristics and experiences, rather than assuming that they are similar to hearing people (Fernyhough, 2014).

However, hearing loss is not the only cause of hearing voices. Some people hear voices that are not related to any external source, such as auditory hallucinations or voice-hearing experiences. These voices may have different characteristics, such as gender, age, tone and content, and may vary in their impact on the person’s wellbeing. Some people find their voices helpful, supportive or creative, while others find them distressing, intrusive or harmful (McCarthy-Jones, 2017).

The exact prevalence of voice-hearing experiences is difficult to estimate, as different studies use different definitions and methods to measure them. However, some researchers suggest that around 2.5% of the world’s population will have extended voice-hearing experiences in their lifetime (McCarthy-Jones, 2017). This means that millions of people around the world hear voices that are not audible to others. The causes of voice-hearing experiences are also complex and multifactorial, and may include biological, psychological, social and cultural factors. Some of the possible factors are childhood trauma, stress, dissociation, psychosis, spiritual or religious beliefs, creativity and imagination (McCarthy-Jones, 2017).

Another source of evidence regarding the multiplicity of the human mind comes from mindfulness practices. We will show later in my thesis that mindfulness is a practice which promotes a type of internal perspective which divides the mind into at least two intelligent aspects. The number of people worldwide who practice mindful meditation is not easy to estimate, as different sources may have different definitions and methods of measurement. However, some studies and surveys have attempted to provide a rough approximation based on various data sources. According to Mindfulness Box (2023), a website that offers mindfulness products and resources, approximately 275 million people meditate around the world. This estimate is based on a combination of government surveys and Google Trends data across multiple languages. The website claims that this is the most accurate answer to date, as it considers the relative popularity of meditation in different countries and cultures (Mindfulness Box, 2023).

Another source, The Good Body (2022), a website that provides health and wellness information, reports that between 200 and 500 million people meditate globally. This range is similar to the one given by Mindworks Meditation (n.d.), a non-profit organization that promotes meditation and mindfulness. Both sources cite the difficulty of finding reliable data on the topic, as meditation is a diverse and evolving practice that may not be captured by conventional surveys or statistics. The Good Body (2022) also provides some insights into the demographics of meditators in the US, based on the National Health Interview Survey conducted in 2017. According to this survey, over 14% of US adults have tried meditation at least once, and women are twice as likely to meditate compared to men. The survey also found that adults aged 45-64 are the age group that meditates the most (The Good Body, 2022).

A third source, CompareCamp (2020), a website that reviews software and services, also mentions the range of 200 to 500 million people who practice meditation globally. However, it also provides some interesting statistics on the benefits and trends of meditation, based on various studies and reports. For example, it states that 70% of people who have been meditating have been engaging in this practice for more than two years, and that meditation can reduce stress by 40%, improve focus by 14%, and enhance creativity by 65%. It also claims that meditation is one of the fastest-growing wellness markets in the world, with an estimated value of $1.2 billion in the US alone (CompareCamp, 2020).

There is no definitive answer to the question of how many people worldwide practice mindful meditation, but some sources suggest that it is somewhere between 200 and 500 million people. This number may vary depending on how meditation is defined, measured, and reported, and it does not indicate exactly how many of them can achieve the state of being an awareness as the watcher of their thoughts. However, we can accept that meditation is a popular activity throughout the world, and can accept the premise that significant numbers of those individuals will have achieved the watching state.

Therefore, it could be concluded that a significant portion of the world’s population actually do experience their internal mind scape as one of a plural mind. and also, that everyone can develop that perception, through practices such as mindfulness.

The essence of human consciousness

My proposed essence of human consciousness is supported by the observation that during mindfulness, it is possible to attain a state where the individual becomes the watcher, and sees thoughts come and go, without being attached to them. This creates an image of the mind being comprised of at least two components: The awareness, which watches the thoughts, and the thoughts themselves.

Mindfulness is a practice of paying attention to the present moment, without judgment or attachment, and observing one’s thoughts and feelings as they arise and pass away. Mindfulness can be seen as a form of self-awareness, which is often considered a key aspect of spirituality and psychological wellbeing.

Mindfulness is defined as “maintaining a moment-by-moment awareness of our thoughts, feelings, bodily sensations, and surrounding environment, through a gentle, nurturing lens” (Greater Good, n.d.). Mindfulness also involves accepting our thoughts and feelings without judging them or believing that they are right or wrong (Greater Good, n.d.). According to self-awareness theory, mindfulness allows us to become aware of ourselves as the thinker, separate and apart from our thoughts (Duval & Wicklund, 1972; Positive Psychology, 2023). By practising mindfulness, we can reduce the conflict between our inner self and outer self, which can cause stress and illness (Verywell Mind, 2023). Mindfulness can also help us align our actions and behaviours with our core values and purpose (Verywell Mind, 2023). According to some mindfulness practitioners and researchers, such as Jon Kabat-Zinn and Daniel Siegel, mindfulness can help people cultivate a sense of “witnessing awareness”, which is a mode of consciousness that is separate from the content of one’s thoughts and emotions. Witnessing awareness can be understood as a pure awareness that is not identified with any mental or physical phenomena, but rather observes them with curiosity and compassion. Witnessing awareness can also be seen as a way of accessing one’s true nature, which is beyond the ego and the conditioned self.

Some spiritual traditions, such as Buddhism, Hinduism, and Advaita Vedanta, also propose similar models of human nature, where the core of a human is a form of pure consciousness or awareness, which is often called the “Buddha-nature”, the “Atman”, or the “Self”. These traditions teach that one can realize one’s true nature by detaching from one’s thoughts and emotions, and recognizing them as impermanent and illusory. In this way, one can transcend the suffering caused by ignorance and attachment, and attain liberation and peace.

Also, it is possible, through mindfulness practices, to perceive that one’s thoughts have differing characters. Some, for example, may be critical, or angry, while others can gentle and supportive. The character of many thoughts, if observed carefully, can be grouped into a perceived set of individual characters. Some people even have names for those characters.

I see this as the simple shape of human consciousness; an awareness, who observes and reacts to thoughts which come from a group of individual characters, each providing thoughts, emotions and feelings to the individual awareness. This is the core of the multiplicity of self.

I would also suggest that these characters can be likened to the Internal Family Systems concept of “parts”, and these are created by the self, as and when needed. They are brought into being to serve particular executive functions, including bodily self-regulation and control. They serve, as part of their functions, to provide us with our thoughts, feelings and emotions. There are multiple routes for receiving these thoughts and so long as there are no dissociations or distortions within the individual’s mind.

When these disparate parts of self are in a healthy state, they form a synchronised, cohesive unity which gives most individuals the impression that they themselves are a single consciousness. This view, in my proposal, is an incorrect assumption, and that the human consciousness typically comprises one awareness and many other self-aspects which provide all thoughts, emotions and feelings.

In the terms of my theory, I suggest that within the human mind these multiple aspects of self, each have their own character, objectives, functions and goals. In a person who has been able to maintain this harmony between these disparate self-aspects, then we call this state, one of wholesome connectedness. This means that the individual’s true-self is available for reflection to the outside world, and all aspects of self are available to that individual to inform them of their true sense of self.

However, in some people, due to their childhood and later experiences, they are caused to reject, deny or modify aspects of their self-concept in such a way that these aspects of self become dissociated or distorted. They have to either modify their own individual self-concept (impose a falsehood), or in some cases become completely rejected from the unified self. There is, therefore have the notion of distorted aspects of self and also dissociated aspects of self.

Because each self-aspect holds the task of carrying out certain executive functions, which may include biological as well as cognitive tasks, the impact of a dissociation may be even more significant to the individual, than simply the denial of an aspect of one’s personality. The implication is, that there may well be physical, as well as intellectual detriments, which could result in physical as well as mental health symptoms.

When an individual rejects an aspect of themselves, another aspect of self may take up the role of enforcing that rejection, yet another aspect of self may take on the role of mediating the impact of that loss of self-aspect on the core self. Thus, we can link our concept to the Internal Family Systems concept of exiles, managers and firefighters.

With my concept of personality distortions, I add the dimension of self-aspects which are still connected to the unity of self, but which are not presenting their true self in their interactions with the whole. Instead, they hold themselves in a state of inner denial and present some modified characteristic. This still represents a loss of self and an undermining of the individual’s true-self, and will cause a loss of confidence in self, since there will be an inner conflict between true-self and the imposed self-concept.

It should be noted that distortions tend to only be created, when the individual takes on and believes some deviation from their true-self. If an individual, knowing their true-self, chose to act out of character, to find the acceptance of another, for example, but was firm in their understanding of their true self, then the unity of self would handle this incongruence. No distortion would be created. The individual, who fully knows themselves, is quite capable of wearing a mask without causing inner conflict. It’s when the individual becomes their mask, that is what sets up the inner conflict and distortions.

Creation of the self-aspects

It is suggested that as a general rule, self-aspects are created on demand, but typically, one for each year of an individual’s life. An exception to this, is in the first year of life, when an additional self-aspect is created for the six-month-old self. I am not suggesting that these self-aspects are created exactly at those internals, rather, they are created on demand, as and when they are needed to take over responsibility for self-regulation at the point the self chooses that those functions need to be devolved.

However, each self-aspect also has the responsibility to act as a “caretaker” for a period of approximately one year, during that time they will serve to collect any discarded personality elements such as distortions or dissociations. They then enforce that rejection of self for the remainder of the individual’s life, or until that personality rule is revoked by the self.

Each self-aspect has the ability to create sub-self-aspects, “mini me’s” who can take over specific self-regulation and personality rules. Thus, in a particularly traumatic year, many sub-self-aspects can be spawned by a single self-aspect.

The self-aspect will serve to act as a spokesperson for their sub-self-aspects in ongoing communications with the self and other self-aspects, and will act as a summariser of all their sub-self-aspects.

My theory suggests that there is a limit to the extent to which an individual self-aspect can support these distortions before themselves becoming disconnected from the unity of self and becoming lost to the unconscious mind. In other words, they can cope when only a small percentage of their self-concept is in denial, however as those denials build up, then there will come a point where they become rejected from the unified self.

Internal and external aspects of self.

With my concept of the human multiplicity, I propose that there are two distinct types of self-aspects; those I call inner self-aspects, who are directly connected to the awareness of self, and who have responsibility for other bodily and cognitive functions of the self. And those that I call outer self-aspects. These are those self-aspects that an individual may become aware of, which seem to come from others. This might include religious or spiritual aspects, but it could also include other people and can include what are commonly called past-lives. These outer-selves form what we call the extended context of the multiple mind, and the following section explains my reasoning behind this concept.

Extended context of the multiple mind

To understand the concept of outer self-aspects, we can firstly review human thought regarding the concepts of “everything is connected,”, and “all is the self”.

The idea that all is one, or that everything in the universe is part of the same fundamental whole, has been expressed by various philosophers, religious traditions, and scientific theories throughout history. Some of the great thinkers who have promoted this idea include:

Plato, the Greek philosopher who was a student of Socrates and a teacher of Aristotle. He was a rationalist who sought knowledge logically rather than from the senses. He proposed the theory of forms, which states that there are ideal and eternal concepts that exist beyond the physical world, and that everything in the material realm is a reflection of these forms (Invaluable, 2019).

Parmenides (c. 5th century BCE), a Greek philosopher who argued that “what is, is uncreated and indestructible; for it is complete, immovable, and without end. Nor was it ever, nor will it be; for now, it is, all at once, a continuous one” (Burnet, 1920/2003, p. 169).

Heraclitus (c. 6th-5th century BCE), another Greek philosopher who famously said, “from all things one and from one all things” (Kahn, 1979, p. 10).

Spinoza (1632-1677), a Dutch philosopher who proposed that “God or Nature” is the only substance that exists and that everything else is a mode or attribute of this substance (Spinoza, 1677/1994).

Einstein (1879-1955), a German physicist who developed the theory of relativity and suggested that quantum physics is compatible with the notion that there is a basic oneness of the universe (Schrödinger, 1958/1992).

In addition, the idea that all is self, or that the self is the ultimate reality, has been promoted by various great thinkers from different traditions and disciplines. Some of them are:

Advaita Vedanta (c. 8th-9th century CE), a school of Hindu philosophy that teaches that the individual self (atman) and the supreme self (brahman) are identical, and that the apparent diversity of the world is due to ignorance (maya). The most influential exponent of this school was Shankara (c. 788-820 CE), who systematized the teachings of the Upanishads and the Brahma Sutras (Shankara, 1995).

George Berkeley (1685-1753), an Irish philosopher and bishop who proposed that all that exists are ideas in the mind of God, and that nothing exists independently of perception. He is known for his motto “esse est percipi” (“to be is to be perceived”) and his arguments against materialism and scepticism (Berkeley, 2008).

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770-1831), a German philosopher who developed a comprehensive system of dialectical idealism, in which reality is conceived as a process of self-development of the absolute spirit, which manifests itself in nature, history, art, religion, and philosophy. He is renowned for his concept of the “dialectic” as a movement of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis, and his idea of the “world-spirit” as the driving force of history (Hegel, 1977).

One of the central ideas of Spiritualism is that the spirit world exists all around and through the material world that human beings inhabit, but in a different dimension, or on a different plane (BBC, n.d.a). This implies that all that exists is connected to self, and therefore the concept of self can be extended to include all that exists. Some of the great spiritualists who have promoted this idea are:

Andrew Jackson Davis (1826-1910), who claimed to have visited the spirit world and described it as a place of harmony, progress, and infinite wisdom, where all beings are interconnected and can communicate telepathically (Britannica, 2021).

Allan Kardec (1804-1869), who codified the doctrine of Spiritism, which teaches that the spirit is immortal and evolves through successive reincarnations, and that the spirit world influences the material world and vice versa (Kardec, 2006).

Many great spiritual leaders have promoted the idea that all that exists is connected to self, and therefore the concept of self can be extended to include all that exists. Here are some examples of such leaders and their teachings:

Deepak Chopra is an Indian American author and speaker who advocates for a holistic view of life that integrates mind, body, and spirit. He believes that the self is not separate from the universe, but rather a manifestation of it. He writes: “The self is not in the world; the world is in the self. Everything that you experience, including other people, is projections of your own level of consciousness” (Chopra, 1994, p. 13).

Paulo Coelho is a Brazilian novelist and spiritual writer who has inspired millions of readers with his stories of adventure and self-discovery. He believes that the self is a part of a larger plan that connects all things in the universe, and that by following one’s dreams, one can align with this plan and find meaning and joy. He writes: “When you want something, all the universe conspires in helping you to achieve it” (Coelho, 1988, p. 22).

Thich Nhat Hanh is a Vietnamese Zen master and peace activist who has taught mindfulness and meditation to millions of people around the world. He believes that the self is interdependent with all phenomena, and that by practising mindfulness, one can realize the inter-being nature of all things and cultivate compassion and understanding. He says: “If you are a poet, you will see clearly that there is a cloud floating on this sheet of paper… If we look into this sheet of paper even more deeply, we can see the sunshine in it… And if we continue to look, we can see the logger who cut the tree and brought it to the mill to be transformed into paper… The cloud is essential for the paper to exist. If the cloud is not here, the sheet of paper cannot be here either… As thin as this sheet of paper is, it contains everything in the universe in it” (Hanh, 1993, p. 3-4).

One of the main teachings of the Dalai Lama is that all sentient beings are interconnected and inseparable from one another, and that this realization can help us overcome our self-centredness and cultivate compassion and happiness. He has expressed this idea in many of his quotes, such as, “Our ancient experience confirms at every point that everything is linked together, everything is inseparable.” (Dalai Lama, 2018, para. 25).

Some of the transcendence theorists who have expressed this idea that everything is connected and therefore self are:

Abraham Maslow: “Transcendence refers to the very highest and most inclusive or holistic levels of human consciousness, behaving and relating, as ends rather than means, to oneself, to significant others, to human beings in general, to other species, to nature, and to the cosmos” (Maslow, 1971, p. 269).

Eckhart Tolle: “Transcending the world does not mean to withdraw from the world, to no longer take action, or to stop interacting with people. Transcendence of the world is to act and to interact without any self-seeking” (Tolle, n.d.).

Adyashanti: “When the eternal and the human meet, that’s where love is born — not through escaping our humanity or trying to disappear into transcendence, but through finding that place where they come into union” (Adyashanti, n.d.).

Viktor Frankl: “Love goes very far beyond the physical person of the beloved. It finds its deepest meaning in his spiritual being, his inner self. Whether or not he is actually present, whether or not he is still alive at all, ceases somehow to be of importance” (Frankl, 1946/2006, p. 37).

These are just some examples of great thinkers, philosophers and spiritual leaders who have promoted the idea that all that exists is connected to self, and therefore the concept of self can be extended to include all that exists. There are many others who have expressed similar views from different traditions and perspectives. The common thread among them is that they invite us to transcend our narrow sense of self and embrace a wider vision of reality that encompasses all beings and phenomena.

It is through these philosophical and spiritual perspectives that we suggest that each individual is connected to every other individual and spiritual being that exists and, furthermore, that those outer self-aspects can communicate with us and influence the reality we experience.

However, I also suggest that this connectivity to the all is experienced in subtle and mysterious ways, and in ways which reflect the notion that those connections between these self-aspects also needs to reflect that those self-aspects are also multiplicities.

Thus, we do not find that everyone on the planet is consciously aware of these connections and influences. And that to become aware of them, typically, people would need to undergo some form of transcendence or awakening. There are, of course, many who do indeed experience such connections. Some have deliberately chosen to walk a path which led them to reach those understandings, however, for some, becoming aware of those connections seems to have been an involuntary, and often unwelcome turn of events.

I am referring here to many people who consider themselves to be unwell, they hear negative voices or have negative experiences which they are convinced come from some agency external to themselves. Sometimes it is from other people, other times it may be ghosts or demons, in fact, there is a huge, almost infinite number of connections, and therefore experiences that any one individual could potentially have due to this notion that we are connected to everything and everyone.

Of course, this suggestion that we are all connected, will come to some as an unwelcome and perhaps frightening concept. It may tend to confirm the reality of some experiences that they might find more reassurance in the notion that they are simply figments of one’s imagination. They may also conflict with their beliefs, and that they may promote within them uncertainty and fear of loss of control.

However, I suggest that there has been a significant amount of thought in this domain, enough for each of us to seriously consider the concepts that I am presenting in this thesis. And also, these connections, when correctly aligned to self, serve to support our individual self. Wholesome connectedness is a state where the individual feels maximum confidence in themselves and knows exactly who they are and what their relationship to the universe is.

Positive and negative aspects of self

I propose that these self-aspects, which form the human mind, can have positive and negative aspects, and that the extent of their positive or negative disposition will affect how they interact with us to form our cognitive experience. For example, a positively disposed self-aspect, may provide a positive supporting role to self, and they may offer up positive suggestions relating to our interests and needs. Conversely, a negatively disposed self-aspect will become a detractor, and may provide unwanted, negative thoughts intended to undermine the individual’s self-esteem and inner peace.

I suggest that inner self-aspects are usually positively disposed from the point of they’re their creation, but that they can become negative based on our interactions with them, through a process of inner denial, characterized through activities leading to self-aspect distortions and dissociations.

Distortions are a process of developing a false self-concept. For example, if through interaction with other, especially significant parties, such as caregivers, we begin to believe ourselves to be unloveable or difficult to love, which is common. Then we may unconsciously tell the self-aspect responsible for expressing love, to deny its expression. This means that it has to withhold its expression of love and distort its concept of true-self for the individual concerned. This results in that self-aspect presenting a distorted view of self to the awareness, and has negative connotations for the individual concerned. Depending on how they came to accept themselves as unloveable, this will result in the individual developing, for example, an avoidant or anxious attachment style.

It is through this process of distortion that we form the basis of all common mental health conditions. For example, depression is the result of distortions, which cause our self-aspects to doubt ourselves, which happens continually, and to also judge ourselves as lacking. anxiety is more related to the distortion of our emotions, as it is often an emotional or feelings-based disorder.

Dissociations are more serious causes of negativity in self-aspects. A dissociation occurs when the entire self-aspect becomes rejected by the self, and it moves out of conscious awareness into the unconscious part of our mind. This usually happens as a result of some traumatic event, where the individual may unconsciously blame a specific self-aspect for causing the trauma, or may not be able to cope with the self-aspect’s expression of self as a result of the trauma. What happens in reality, is that the awareness effectively refuses to talk to that self-aspect, it no longer wants any communication with it, it puts up a wall blocking further conscious communication. The self aspect will therefore find itself isolated, and it will build up resentment over time for that isolation.

When an aspect of self becomes dissociated, there is often a double negative outcome; firstly, the individual’s self-concept takes on a significant distortion, secondly, the self-aspect that has been exiled may build up resentment, and over time, find ways of showing its resentment towards the awareness in the form of negative thoughts, voices, emotions or feelings. For example, when a loved one causes a child serious abuse, the child may blame itself for loving that caregiver, and that blame could result in a total rejection of that loving self-aspect. Initially, the child will probably develop an avoidant or anxious attachment style, but of a more serious nature than in the earlier example. This maladaptive attachment style is far for likely, for example, to turn into a personality disorder. On top of this, that resentment that is set up within the dissociated self-aspect may well turn up later in life, through negative thoughts, voices, triggers for anger, even psychosis, and could see the personality disorder become accompanied by a psychosis related disorder.

It follows, then, that each individual with personality dissociations will either have lost touch with aspects of their personality, or have aspects of their personality which are distorted, and no longer true to self. I have proposed in my wholeness theory of self-esteem that an individual who finds themselves in this state, depending on the extent and nature of the dissociations, will find it difficult to attain or maintain a high level of self-esteem. That the more dissociations and distortions of personality they have, then the lower the base-level of their core self-esteem will be.

An individual, whose core self-esteem is very low, will find themselves in a very needy place. They will tend to desperately reach for anything that might give them some modicum of self-esteem boost, or they may just as desperately seek to avoid their feelings of worthlessness with distraction, even drug related oblivion. It is through this behaviour that the relationship with the individual’s other self-aspects becomes even further distorted, as they take on roles of providing distractions, or satisfying addictions.

This process of creating internal distortions and rejections of the individual’s self-aspects has other implications. These are in relation to their outer self-aspects: Depending on our relationship to them, and also their own core aspects. some outer self-aspects can be negative. For example, an outer self-aspect that identifies as a demon can be thought of as a negative self-aspect. One hidden aspect of our dissociated inner self-aspects, is that they can work with outer self-aspects in the furtherance of their own goals and wishes. This is often where the more significant types of psychosis come from; the rejected and negatively disposed self-aspect, chooses to work with a negative outer self-aspect to increase the impact of their combined pressure on the individual.

This negativity “pact” between our inner and outer self-aspects is often the cause of some of our more bizarre and extreme mental health conditions. Imagine, for example, a disgruntled inner self-aspect deciding that its negative impact on the individual concerned is inadequate, and deciding to recruit a negative self-aspect of a neighbour to make that individual hear the voice of their friend, talking bad about them. The neighbour will not be consciously aware of this, and may not even be aware that they have negative self-aspects of their own. The impacted individual, if they react to this voice of their neighbour, say, by confronting them, will find themselves branded as “mad”, and may well find themselves getting angry, as the neighbour denies what the individual considers to be the truth. This situation happens a lot, and often sees the impacted individual paying a forced visit to the local mental health hospital.

It can be seen, then, that this theory of the human multiplicity introduces an entirely new way of understanding the working of the human mind. It underlines where our mental health disorders come from, how they can deteriorate, and the resulting impact on our self-esteem. Given this understanding, we can also continue to propose an approach which can lead to the effective correction of the problem.

Healing distortions and dissociations

The approach to healing these distortions and dissociations, both of those inner self-aspects and of the outer self-aspects, will usually present itself to the individual as somewhat counter-intuitive. The question is, what do we do about those aspects of ourselves who hate us, and sometimes even want to kill us? The simple answer, is to love them.

The secret to understand, is that the primary driver, for all self-aspects, is that they want to be loved. They want to be acknowledged, be respected and be understood. They also want to express their whole truth. Remember, it was this rejection of their truth that got us in that negative relationship in the first place; we chose to ask them to lie about themselves, to suppress their feelings and emotions or some other aspect of their expressed truth. This was the cause or the breakdown of our relationship with them, and as a result of that breakdown, we now find ourselves with those negative thoughts, feelings, emotions, voices etc.

The solution, is to accept you were wrong to reject their truth, and to negotiate to bring them back into the cohesive totality of self, to tell them that in future you will always express their truth. As part of that negotiation, they will probably want you to prove your integrity by allowing the expression of what was suppressed in the past. They will need to be convinced that you are serious, and that you take your future relationship with them as one of upmost importance.

Regarding those outer self-aspects, the approach, again counter-intuitively, is exactly the same. Remember – all is self, and that all the self is to be loved.

The idea that all is self, and all the self is to be loved, is not a new one. It has been expressed by various philosophers, mystics, and spiritual teachers throughout history. Here are some quotes that convey this message in different ways:

“You yourself, as much as anybody in the entire universe, deserve your love and affection.” – Buddha

“Love yourself first, and everything else falls into line. You really have to love yourself to get anything done in this world.” – Lucille Ball

“The most powerful relationship you will ever have is the relationship with yourself.” – Steve Maraboli

“Your task is not to seek for love, but merely to seek and find all the barriers within yourself that you have built against it.” – Rumi

“You are a divine being. You matter, you count. You come from realms of unimaginable power and light, and you will return to those realms.” – Terence McKenna

“Everything in the universe is within you. Ask all from yourself.” – Rumi

“You are the universe, expressing itself as a human for a little while.” – Eckhart Tolle

“You are not IN the universe, you ARE the universe, an intrinsic part of it. Ultimately, you are not a person, but a focal point where the universe is becoming conscious of itself. What an amazing miracle.” – Eckhart Tolle

“The kingdom of God is within you.” – Jesus Christ

Thus, the solution to correcting one’s relationship with any self-aspect, inner or outer, is to establish a loving relationship with them. Often this will involve a drama, where that aspect of self gets to decide whether they trust the core self, and the core self gets to know more about that self-aspect. If one approaches this with integrity and a commitment to heal, then the result will be, that the individual will integrate that aspect of self into their concept of self. In the process, the self-aspect will “flip” from negative to positive, the inner critics will turn into inner supporters.

It should be noted, that outer self-aspects sometimes do not need the collusion of our inner self-aspects to affect us. Sometimes there are other reasons for their involvement with us. Whilst it is true that having 100% of our inner self-aspects in a harmonious relationship with the totality of the self means that we are protected from spurious attention from random negative outer self-aspects. There are some circumstances which mean we will get significant attention from some outer-aspects. One of those circumstances, oddly, is when we have asked for it as part of our incarnation planning. This may seem strange, but the concept is, that, before our birth, we made agreements with specific outer self-aspects so that they may “help” us achieve our incarnation goal. Sometimes this includes the attention of negative self-aspects, determined to wake us up from our illusion of simply being a “human”.

This is the mystical nature of our relationship with our many self-aspects. It is also a key part of self-transcendence. It is the recognition of the fact that everything is connected, and that everything is therefore self, and the realisation that the only choice, is to love yourself.

Implications for psychology, ethics, politics, and art

In psychology, multiplicity can be understood as a general phenomenon of identifying as multiple. Multiplicity can also be seen as a personality style that reflects the adaptation to different contexts and roles in one’s life (Braude & Carter, 2010). Multiplicity can offer insights into the development, diversity, and dynamics of human personality, as well as the potential benefits and challenges of having multiple selves. The potential in relation to the diagnosis and understanding of those who hear voices or experience other negative health symptoms that appear to come from outside themselves will need to be considerably re-evaluated.

In ethics, multiplicity can raise questions about the moral status and rights of each personality or self within a person. For example, if a person commits a crime while being in a different personality state than their usual one, are they accountable for their actions? How should they be treated by the law and society? How should they relate to their other selves and to other people? Multiplicity can also challenge the assumptions and values of ethical theories that rely on a unified and consistent self.

In politics, multiplicity can have implications for the representation and participation of people with multiple selves in democratic processes. For example, how should people with multiple selves vote or run for office? How should they be counted in censuses or surveys? How should they express their interests and preferences in public debates? Multiplicity can also offer alternative perspectives on political issues and conflicts, as well as possibilities for dialogue and collaboration among diverse groups.

In art, multiplicity can be a source of inspiration and creativity for artists who explore the multiplicity of their own or others’ minds. For example, some artists may use different media, styles, or genres to express their different selves or personalities. Some may create works that reflect the interactions or transformations among their multiple selves. Some may also use art as a way of communicating or integrating their multiple selves. Multiplicity can also enrich the appreciation and interpretation of art by allowing for multiple meanings and perspectives.

Conclusion

I believe that within this thesis I have presented sufficient evidence and thought to strongly suggest that the notion of the human as a multiplicity is an idea that needs to be taken seriously, by the world of psychology, and by society as a whole. If correct, and I strongly suggest it is, then there are significant implications as to how each of us as individuals interact with our mind, with others and with the wider aspects of the reality we observe around us. The implications regarding the understanding and diagnosis of mental health disorders are also significant, and we suggest that an acceptance of my theory, by psychologists and psychiatrists, would cause a serious rethink as to how such cases are understood and treated.

I do support the idea of informed further investigation, if only to help confirm my proposed structure of the mind in the thinking of others. I also recognise the certain resistance this concept will get from some quarters. New concepts, even those with a history spanning thousands of years, are not always found to be acceptable by the majority.